|

God is often portrayed extremely negatively in the Old Testament. For example, in the Book of Nahum God is pictured as being responsible for the most horrifying violence imaginable. This negative portrayal of God is also found in the Book of Job. God is responsible for the suffering that his righteous servant Job, has to endure. He is even manipulated by the satan to allow him free reign in attacking Job. God even acknowledges that the misery and pain inflicted on Job, was for no reason. Job’s children are killed in order for God to prove a point, and in his response to Job’s suffering, he doesn’t even address the issue of Job’s suffering. This is a picture of a very cruel, vicious God. This article investigates the negative, disturbing images of God in the Book of Job. Are these images of God who God really is, or is the God of Job a literary construct of the author? The focus of this study is on the prologue and epilogue to the book, as well as the speeches of God in Job 38–41.

The God of the Old Testament is arguably the most unpleasant character in all fiction: jealous and proud of it; a petty, unjust, unforgiving control-freak; a vindictive, bloodthirsty ethnic cleanser; a misogynistic, homophobic, racist, infanticidal, genocidal, filicidal, pestilential, megalomaniacal, sadomasochistic, capriciously malevolent bully. (Dawkins 2006:51)These words from well known atheist Richard Dawkins are shocking and Dawkins is obviously biased in his description of God, but the fact remains that the images of God in the Old Testament are often extremely negative. When one reads the Old Testament, one is often confronted with a picture of God that is totally different from the one we have learned at mother’s knee and in Sunday

school.1 A comparison between the Old Testament and the New Testament also allows for often completely different pictures to emerge. The God of the Old Testament is not always a very ‘nice’ God, whereas in the New Testament God is portrayed as the God of love who in Jesus Christ reconciled the world to

himself.2 In the Book of Nahum for instance, God is portrayed as an extremely violent God.3 Not only is he the instigator of violence, but he is often the perpetrator (cf. Maré & Serfontein 2009:175–185). The images utilised by the author of Nahum for God’s violence are extremely shocking and offensive. These violent acts of God reinforce the idea that the God of the Old Testament is unjust and bloodthirsty. In the article referred to, the authors argued that humankind often creates gods that serve its needs and ideologies. Thus, the God of Nahum becomes a rhetorical-ideological construct of the ideologies of Nahum’s society (Maré & Serfontein 2009:176). Terence Fretheim (2005:220) has pointed out that the portrayal of God in the Book of Job is troublesome for many readers of the biblical story. For instance, God sets his servant Job up for suffering, he is even manipulated by ‘the satan’ to allow him free reign to attack Job. Job’s children are sacrificed in order for God to prove a point. Throughout the dialogue sections of the book God are hostile, cruel and inaccessible for Job, and when he eventually responds to Job’s suffering, he does so with two long speeches that do not address the issue of Job’s suffering. As Fretheim rightly argues, God’s response would result in a failing grade in most (if not all) pastoral counselling classes (2005:220). The purpose of this article is thus to investigate the negative, disturbing images of God in the Book of Job and questions that arise from the perturbing portrayal of God include the following: What kind of God plays chess with the satan for the life of one of his servants? Is this God trustworthy? Can he be manipulated? Does God really allow one of his own to suffer horribly, just to prove a point and win a bet? Is the God of Job a literary construct? These are some of the questions that will be addressed in the article. The focus of study will be the prologue and epilogue to the book, as well as the speeches of God in Job 38–41.

|

The genre and date of the Book of Job

|

|

The first issue I want to address is the genre (specifically whether the book should be read as fact or fiction) and the date of the Book of Job. The prose framework of the book should not be understood as historical literature or as a biography of a man called Job. Rogerson (2010:85) argues that the prologue and epilogue are narratives that provide an intelligent framework for the dialogues between Job and his friends. He is indeed correct that the dialogues would not make sense without this (fictional) narrative framework. It is possible that underlying the story of Job is a real experience of intense suffering and that Job was a legendary person known for his piety, but the story is probably fictional. The omniscience of the narrator particularly points in this direction. The setting of the story is the ancestral time in an unidentifiable land called Uz. Job performs his own sacrifices (Job 1:5), his possessions are measured similar to Abraham and Jacob in sheep, oxen, camels, asses and servants (Job 1:3); his land was subject to raids from pillaging tribes (Job 1:15–17); his lifespan of 140 years is matched only in the Pentateuch (Job 42:16); the epic nature of the prose story finds its nearest parallels in the patriarchal stories of Genesis and in Ugaritic literature (LaSor, Hubbard & Bush 1996:472). The Book of Job can rightly be called ‘once upon a time’ literature (Fretheim 2005:221). The book forms part of the corpus of Wisdom Literature of the Old Testament and therefore it has a didactic purpose. Addressing the issue of suffering, Job can be described as a ‘what-if book, a let’s suppose-for-the-sake-of-argument book’ (Fretheim 2005:221). A different viewpoint is held by Brueggeman (2003:519) who suggests that there are key indicators that point toward historicity. He argues that the opening verses of the book adopt a historical note and regards the reference in Ezekiel 14:14, 20 to Job alongside Noah and Daniel as sufficient proof for the historicity of the book. His arguments are, however, extremely weak and can be dismissed out of hand. A feature of good fiction is that it presents itself as if

historical4 and the historicity of Noah and Daniel is of course not beyond doubt. There is no real consensus amongst scholars for the dating of the book. Suggestions range from the time of the patriarchs to post-exilic times, although most scholars today do not accept an early date for the composition. Janzen (1985:5) thinks that the book was probably written in post-exilic times and the problems it addresses arose from the tension between the upheaval experienced during the exile and the religious traditions of Israel. Hartley (1988:18–20), after a thorough discussion of the various options that have been offered, opts for the 7th century BCE as the probable time of origin. Perdue’s (2008:118) proposal for the date of the book seems convincing. The book probably developed over a period of two centuries, beginning with the Babylonian exile and concluding in the late Persian period. The narrative may have been composed during the first temple period, serving a didactic function. Parallels with Babylonian texts (cf. Perdue 2005:131–133),

Ezekiel’s reference to Job, and the many Aramaisms point to an exilic date for the poetry section. Other considerations include the reference to ‘the satan’ in Job 1–2, not as a personal name but as an office, the likely dependence of Job 3 on Jeremiah 20:14–18, and the similarity in style and vocabulary of the dialogues with Second Isaiah. The final redaction possibly occurred during the late Persian period.

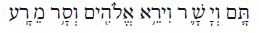

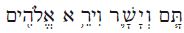

The prologue tells the well known story of a righteous man called Job. The Hebrew text is extravagant in its description of this man. No less than four different words and phrases are used to refer to him (Job 1:1):

Job is pure and blameless  , he is upright, just and righteous , he is upright, just and righteous

, he is a man who fears God

, he is a man who fears God

and someone who turns away from evil

and someone who turns away from evil

. He is prosperous, richer than anyone else, blessed with seven sons5

and three daughters and multitudes of cattle and many slaves. Read against the background of retribution theory, one can indeed say that this man is blessed for his righteousness.

Job is portrayed as a loving and caring man, someone who regularly sacrifices on behalf of his children on the chance that they might have sinned at one of their regular meals when they

got together to eat and drink. Job as ‘God-fearing’ and God as ‘Job-blessing’ suggest a relationship that is a ‘closed system’ where God is portrayed as ‘a

nurturing God of stability’ (Boss 2010:22).

. He is prosperous, richer than anyone else, blessed with seven sons5

and three daughters and multitudes of cattle and many slaves. Read against the background of retribution theory, one can indeed say that this man is blessed for his righteousness.

Job is portrayed as a loving and caring man, someone who regularly sacrifices on behalf of his children on the chance that they might have sinned at one of their regular meals when they

got together to eat and drink. Job as ‘God-fearing’ and God as ‘Job-blessing’ suggest a relationship that is a ‘closed system’ where God is portrayed as ‘a

nurturing God of stability’ (Boss 2010:22). One day, the sons of God appeared before God. This recalls the mythological assembly of the gods that Psalm 82 speaks of. God is here portrayed as the king who stands at the head of the divine

assembly.6 On this day, one of those present, was ‘the satan’

.

This is clearly not a personal

name, but a designation and one should be careful not to read the later belief in the existence of the evil one, Satan, into this text.7 The satan acts as an accuser and is also a member

of the divine council. What is obvious in the text is that the satan should not be understood as an opposing force, equal in strength to God. The satan can only do what God allows him to do. He needs

God’s permission for the execution of his plan. .

This is clearly not a personal

name, but a designation and one should be careful not to read the later belief in the existence of the evil one, Satan, into this text.7 The satan acts as an accuser and is also a member

of the divine council. What is obvious in the text is that the satan should not be understood as an opposing force, equal in strength to God. The satan can only do what God allows him to do. He needs

God’s permission for the execution of his plan. The appearance of the satan is the event that starts everything. God engages the satan in a conversation and asks where he has been. The answer is that he has been roaming and wandering across the earth.

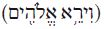

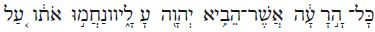

Then God boasts about one of his servants, the man Job, the man who is

.

God uses exactly

the same description of Job as the narrator of the story did. God is portrayed here as a proud parent who brags about a favourite child. Then the satan shows himself to be quite knowledgeable about

retribution theology and he says to God that the only reason for Job’s faithful service is the fact that he has prospered as a result of his service to God. Balentine (2003:358) aptly says that the

implication of the satan’s question is that God has defined Job’s world and protected his life in a way that ensures Job’s complete and utter devotion. The satan challenges God to remove

this protection and take away what Job has gained from his religion, and surely, it is expected that that will be the end of it: he will curse God and no longer serve him. God accepts the challenge and he

allows the satan to take away everything that Job has.8 .

God uses exactly

the same description of Job as the narrator of the story did. God is portrayed here as a proud parent who brags about a favourite child. Then the satan shows himself to be quite knowledgeable about

retribution theology and he says to God that the only reason for Job’s faithful service is the fact that he has prospered as a result of his service to God. Balentine (2003:358) aptly says that the

implication of the satan’s question is that God has defined Job’s world and protected his life in a way that ensures Job’s complete and utter devotion. The satan challenges God to remove

this protection and take away what Job has gained from his religion, and surely, it is expected that that will be the end of it: he will curse God and no longer serve him. God accepts the challenge and he

allows the satan to take away everything that Job has.8 Then one day, the unthinkable happens. Job, the righteous, blameless man who fears God and does not follow evil, receives message after message after message of disaster following disaster. He loses his

cattle and donkeys, his sheep and his servants, his camels and horror above horrors – his children. They all die, and Job, the righteous man, is robbed of everything he had.9 This is an extremely disturbing image of God. He accepts a bet on the life of one of his own.10 What kind of God is this, who gambles with the life of this righteous man? What kind of God is

this, who allows the satan to attack Job and even take away the lives of his children, just to prove a point? It seems as if this God can easily be manipulated into doing all kinds of horrible deeds. All

that is needed is the right wager, and the proud parent turns into a monster. It seems that this God is not trustworthy because he will at the throw of a dice allow the most horrible suffering in the life

of one of his own. God is portrayed as being responsible for evil in this world. It is his fault that Job loses everything; it is his fault that in one fell swoop, Job’s children all die, and in an

age where offspring were regarded to be a sign of blessing, Job becomes a cursed man. Rogerson (2010:144–145; cf. also Goldingay 2006:78–80) rightly points out that there appears to be a dark side to God, a side that puzzles and makes us uncomfortable because it does not conform

to the image humans have of God. God is sometimes, as is the case here in Job, associated with evil, in the sense that he allows certain calamities to happen to afflict the world, his people particularly,

and as happens here, individuals. He asserts that as difficult as these portrayals of God might be for the life of faith, it may well be an essential part of the God-human relationship. Without this dark

side to God’s character he might become a tool in a one-sided relationship. Job is very fatalistic in his response to this tragedy: in accordance with the customs of the day (cf. Clines 1989:34–35), he shaved his hair, tore his clothes, but then he fell down and he worshipped. He

worships the God who is responsible for his pain and suffering, he worships the God who is directly responsible for his losing all his possessions, and he worships the one who is to blame for the death of his

children. This response plainly demonstrates that in the mind of the narrator, Job is indeed blameless and righteous. The narrator notes that Job’s response indicates that he did not sin before God, Job

accepted his fate, he accepted the death of his children, he accepted the loss of everything he had. Job’s acceptance of all these horrible events in his life, indicates that he did not sin. Again, this

portrait of God is extremely disconcerting. Is he the kind of God who would punish a righteous man if he ranted and raved at the death of his children at the hand of this God? The story gets worse. One day, the sons of God again appear before him, with the satan also amongst them. Again God asks the same questions as he did in chapter 1:7–8. He brags with his righteous servant,

again referring to him as

.

He is again the proud parent, boasting about a

favourite child. Although he has killed the children of the righteous and blameless man Job, he boasts about the fact that this suffering man has persevered in his piety. He at least acknowledges that

the satan has instigated his attack on Job, he concedes that he has been manipulated into allowing evil to overcome this favourite servant, this blameless man.11 The fact that this happened

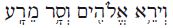

‘for no reason’ .

He is again the proud parent, boasting about a

favourite child. Although he has killed the children of the righteous and blameless man Job, he boasts about the fact that this suffering man has persevered in his piety. He at least acknowledges that

the satan has instigated his attack on Job, he concedes that he has been manipulated into allowing evil to overcome this favourite servant, this blameless man.11 The fact that this happened

‘for no reason’  adds to the absolute horror of this story. Balentine (2003:360; cf. also Seibert 2009:31) is justly shocked when he writes

that this admission of God, that he set out to destroy Job for no purpose, is conceivably ‘the single most disturbing admission in the Old Testament, if not in all Scripture.’ All his cattle –

lost, all his servants – gone, seven sons and three daughters – dead, and all this needlessly, for no reason. adds to the absolute horror of this story. Balentine (2003:360; cf. also Seibert 2009:31) is justly shocked when he writes

that this admission of God, that he set out to destroy Job for no purpose, is conceivably ‘the single most disturbing admission in the Old Testament, if not in all Scripture.’ All his cattle –

lost, all his servants – gone, seven sons and three daughters – dead, and all this needlessly, for no reason. Then the incomprehensible happens, God allows himself to be manipulated again. Instead of reversing the earlier damage he had done to Job, he inflicts much greater suffering on Job (cf. Whybray 2008:30). The

satan says to God that if He stretches his hand out against Job and touches him in his body and in his health, then surely, Job would curse God. One would think that God would not allow himself to be so blatantly

manipulated, but he lets it happen again. The proud parent becomes the monster once again and allows the satan to attack his servant, stopping just short of killing him. At least Job is shown more grace than his

children were – he lives, they died. The satan continues his attack on Job, and he strikes him with sores  all over his body.12 His only recourse was to sit in ashes, scratching

himself with a potsherd.13 His wife wanted him to curse God and die, yet Job refused, calling her a fool.14 He then stated that if one is willing to accept the good from the hand of God, one

should also be prepared to accept evil from him. Here the narrator lets Job utter the belief that God was responsible for evil in this world. God is liable, he is the reason for the suffering of Job, and he is to

blame.15 all over his body.12 His only recourse was to sit in ashes, scratching

himself with a potsherd.13 His wife wanted him to curse God and die, yet Job refused, calling her a fool.14 He then stated that if one is willing to accept the good from the hand of God, one

should also be prepared to accept evil from him. Here the narrator lets Job utter the belief that God was responsible for evil in this world. God is liable, he is the reason for the suffering of Job, and he is to

blame.15 Three of Job’s friends then came to sit with him to comfort him. So great was his suffering, the suffering that God was responsible for, the suffering that God brought upon him in order to win a bet, that the

text states that they did not recognise him. They sat with him for seven days and nights, not saying a word, out of respect for the intensity of his pain, his sorrow, his misery.

After the suffering that he had caused his servant, God keeps silent for the next 35 chapters. Job and his friends debated his suffering back and forth, and Job issued a brave challenge to the God who,

although Job does not know it, is responsible for his pain (Chapter 29 – Chapter 31). Elihu then takes the stage in Chapter 32 to Chapter 37, and finally, God breaks his silence in Chapter 38. At this point, one would expect God to admit his role in Job’s suffering. One would expect God to stand up for what he did to Job. One would expect an explanation from God, outlining how he has been swayed

by the satan, and how not once, but twice, he was manipulated into allowing the satan to harm Job, to take away everything he had, to kill his children, to cause disease in his body. One would expect God to

acknowledge that he was responsible for the evil that befell Job. At least ’ then Job might have understood that he was at the mercy of a wager between God and the Satan. However, not once

does God provide such an explanation, not once does he admit his role in this tragedy, not once does he accept responsibility for what he has done to Job, not once does he show regret for what he has done.16

The speeches of God, in fact, seem to be completely unrelated to anything that has gone before (cf. Mathewson 2006:136–137). Instead, God flings rhetorical question after rhetorical question in the face of Job. The Creator questions one of his creatures on creation. Habel (2004:28) rightly says that God’s speeches serve to

intimidate Job and to bring him to his knees. Of course, Job cannot answer, of course, Job does not know, of course Job does not understand; he is not a scientist, just a righteous man who feared his God, the God

who, unbeknown to him, is responsible for all his suffering. Surprisingly, humanity as the apex of God’s creative work, ruling over the work of his hands, is not found in God’s speeches. The creation

of humankind is indeed ignored. God is portrayed here as the Creator, the Almighty, the Omniscient, the one who holds everything in his hand and has everything under his control. The image that the author provides for God here is that of the

sovereign, holy God who is answerable to no one. He is God, and therefore he can do as he pleases. Yet to my mind God is also portrayed as being unfair. Does he really expect Job to provide him with answers? He,

who refuses to provide an explanation to Job for his suffering, now expects Job to give him an explanation for the mysteries of the universe! He seems to be saying to Job that he does not understand the mysteries

of the universe, yet he lives with it. So Job will just have to live with the mysteries of his suffering as well.

It is very interesting to note that the portrayal of the character of Job is different in the prologue and the epilogue if compared to the description of Job of the middle, poetic section. In the poetry section

Job struggles with God, and is unafraid to take him to task. In the prologue and epilogue, Job does not question God at all, but meekly accepts everything that God puts in his path. Here, in the epilogue, Job

surrenders to God. He acknowledges that God is the Almighty who can do as he pleases, he concedes that he has spoken about things that he does not understand, and therefore he asks God to instruct him. Then he

confesses that his knowledge of God up to this point was based on what he had heard; now that his eyes have seen God, this puts his relationship with God on a different level from what has gone before.17 What appears strange to me is that Job then repents and shows regret for what he has done. Is he sorry that he questioned God, sorry that he struggled with him; sorry that he took him to task for what God had done to

him? Should God not show regret for being responsible that Job lost everything he had, even his children? God did not even provide an explanation for Job’s suffering, yet Job has to repent? Once again, a very

negative picture of God. It seems, however, that Job’s confession counts in his favour, because God addresses Job’s three friends and tells them that he is angry with them because they did not speak what was right about him. It is

puzzling that God now says that Job spoke what is true about him.18 If Job spoke the truth about God, why then did he rebuke him in the speeches in Chapters 38 to Chapter 41 and why did Job have to repent?

This supports the idea that God is portrayed as being capricious, unpredictable and even unreliable. God then tells the friends to take seven bulls and seven rams as an offer for Job to sacrifice on their behalf. Job is accepted by God, therefore his prayers and sacrifice would be received. God then changes Job’s

destiny and he receives twice as many possessions as he had before. Verse 11 reiterates the belief that God was responsible for evil when the author states:

.

Yahweh is here explicitly mentioned as the author of Job’s misery and sorrow. But now, Job is once again blessed.

Not only does he have twice as many possessions as before, but he also has seven sons and three daughters, the same as he had before.19 Seemingly, the book has a ‘happy ending’.

However, can the ten new children really compensate for the loss of the ten children at the beginning of the book? Does God’s favour here exonerate him from what he did to Job at the beginning of the

story? I think not. It actually reinforces the image of God as being capricious, fickle and cruel. .

Yahweh is here explicitly mentioned as the author of Job’s misery and sorrow. But now, Job is once again blessed.

Not only does he have twice as many possessions as before, but he also has seven sons and three daughters, the same as he had before.19 Seemingly, the book has a ‘happy ending’.

However, can the ten new children really compensate for the loss of the ten children at the beginning of the book? Does God’s favour here exonerate him from what he did to Job at the beginning of the

story? I think not. It actually reinforces the image of God as being capricious, fickle and cruel. When one reads the Book of Job against the background of wisdom thinking regarding retribution theory, it seems to me that something odd has happened here. Retribution theory upheld the belief that one’s destiny

in life was indicative of whether one should be seen as righteous or ungodly. When Job lost everything, his friends believed that the reason for this tragedy was some hidden sin in Job’s life. Job protested against

this with all his might; he knew he did not sin and thus he wasn’t being punished. Verses 7–8 confirm that the friends were wrong about God – he does not reward or punish depending on good or bad

behaviour. Yet, here we find Job, once again being blessed by God, and Job is the one who spoke what was right. Does this mean that retribution theory is after all true? Or does God bless just because he wants to,

just like he did evil because he wanted to prove a point? Whybray (2008:192) rightly says that God’s reaction should come as no surprise because it has already been established that he is unpredictable and behaves

as he likes. Rogerson (2010:166) argues for the first of these possibilities when he writes that Job’s friends are actually proven right ‘in that the world is a moral universe in which good is ultimately rewarded.’

Thus the point Job wanted to make is undermined. Carson (2006:155) argues for the opposite. He maintains that Job’s change of fortune at the end of the book should not be understood as rewards that he had earned for

his continued faithfulness, but that they are simply blessings given as God’s free gift.20 Perhaps one could argue that Yahweh’s freedom to act as he pleases allows him to act destructively, but

that the same freedom also permits him to renew his blessings.21 Taking into consideration that Job’s whole life is a repudiation of the doctrine of retribution, Habel (2004:35) upholds the idea of

‘restorative justice’ instead of ‘retributive justice’. He asserts that Job’s reversal of fortune should rather be understood as divine restoration and not as reward for righteousness.

Perhaps the text is purposefully ambiguous on this issue. Perhaps the text allows for the restoration of Job’s fortune as a consequence of God’s undeserved favour, but perhaps the capriciousness of God in

the story of Job, allows for a reading that confirms retribution theory.

How then, should we understand the God of Job? Who is He? If one perceives the Bible to contain God’s self-revelation to humankind (Möller 1998:85)22 then the portrayal of God in the Book of

Job forms part of his self-revelation. If this viewpoint, that the account of God’s self-disclosure is found in the Bible is correct, then we will have to accept that God is a child killer, responsible for evil,

responsible for the horror of Job’s suffering; someone who can be manipulated by one of his underlings to inflict pain and misery on one of his own without reason; someone who bets on the life of a righteous man;

someone who is responsible for intense agony just to prove a point; someone who does not provide explanations for his misdeeds; someone who does n ot show regret for the horror he has caused; someone who is cruel,

vicious, capricious, fickle, and unreliable. Is this a true picture of who God is? Seibert (2009:170–181) proposes that the Old Testament descriptions of God should not be understood as aspects of his self-revelation, but as human depictions of God. This means that not every image of God

reflects who he really is. It is therefore necessary to distinguish between the characterisation of God in the Bible and the character of God in reality. Consequently, it is required that we differentiate between

the ‘textual God’ and the ‘actual God’.23 The textual God is a literary representation; the actual God is a living reality.24 I have already indicated that I read the Book of Job as a fictional story; therefore to my mind Seibert is correct in distinguishing between the textual God and the actual God. The textual God is thus a literary

creation of the author and consequently God becomes a fictional character in a story.25 In the story of Job the portrayal of God should thus not be understood as a revelation of who God really is, but

he is a literary construct created by a human author to fulfil a specific role in the narrative. The author of Job created the character of God as part of his protest against conventional wisdom thinking and retribution

theory, which understand God to be the one, who blesses the righteous and punishes the wicked. Protesting against this simplistic worldview, Job’s God becomes a harsh and forbidding character who punishes the

righteous without reason. Job’s God thus turns out to be a rhetorical construct of Job’s author in order to serve the writer’s theological purpose. This reading of the portrayal of the God of Job

creates the possibility to reject these images as a true picture of who God really is.

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no financial or personal relationship(s) which may have inappropriately influenced him in writing this paper.

Balentine, S.E., 2003, ‘For no reason’, Interpretation 57(4), 349–369.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002096430005700402Boss, J., 2010, Human consciousness of God in the Book of Job: A Theological and Psychological commentary, T & T Clark, London. Brown, W.P., 1999, ‘Introducing Job: A journey of transformation’, Interpretation 53(3), 228–238.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/002096439905300301 Brueggeman, D., 2003, ‘Sweet singers and sages: Israel’s poetry and wisdom’, in W.C. Williams (ed.), They spoke from God: A survey of the Old Testament, pp. 511–554,

Gospel Publishing House, Springfield. Carson, D.A., 2006, How long, O Lord? Reflections on suffering and evil, Baker, Grand Rapids. Clines, D.J.A., 1989, Job 1–20, Word, Dallas. (World Biblical Commentary 17). Cornelius, I., 2009, ‘Job’, in J.H. Walton (ed.), Zondervan Illustrated Bible Backgrounds Commentary, vol. 5, pp. 246–301, Zondervan, Grand Rapids. Dawkins, R., 2006, The God delusion, Black Swan, London. Fretheim, T.E., 2005, God and World in the Old Testament: A Relational Theology of Creation, Abingdon, Nashville. Gericke, J.W., 2004, ‘Does Yahweh exist? A philosophical-critical reconstruction of the case against realism in Old Testament theology’, Old Testamanet Essays 17(1), 30–57. Goldingay, J., 2006, Isreal’s faith: Old Testament Theology, vol. 2 , InterVarsity, Downers Grove. Habel, N.C., 2004, ‘The verdict on/of God at the end of Job, in E. Van Wolde (ed.), Job’s God, pp. 27–38, SCM, London. Hartley, J.E., 1988, The Book of Job, Grand Eerdmans, Rapids. (New International Commentary on the Old Testament). Janzen, J.G., 1985, Job, John Knox, Atlanta. (Interpretation). Kamp, A., 2005, ‘Gods wegen zijn ondoorgrondelijk: Beelden van God en mensen in Job 1-3’, in E. van Wolde (ed.), De God van Job, pp. 12–24, Uitgeverij Meinema, Zoetermeer. LaCocque, A., 2011, ‘Justice for the innocent Job!’, Biblical Interpretation 19, 19–32. LaSor, W.S., Hubbard, D.A. & Bush, F.W., 1996, Old Testament survey: The message, form and background of the Old Testament, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. Maré, L.P. & Serfontein, J., 2009, The violent, rhetorical-ideological God of Nahum, Old Testament Essays 22(1), pp. 175–185. Mathewson, D., 2006, Death and survival in the Book of Job: Desymbolization and traumatic experience, T & T Clark, London. Möller, F.P., 1998, Understanding the greatest of truths, Van Schaik, Pretoria. (Words of light and life vol. 1). Ngwa, K.N., 2005, The Hermeneutics of the’Happy’ ending in Job 42:7-17, De Gruyter, Berlin. (Beihefte zur Zeitschrift fűr die alttestamentliche Wissenschaft, Bd. 354). Perdue, L.G., 1994, Wisdom & Creation: The Theology of Wisdom Literature, Abingdon, Nashville. Perdue, L.G., 2008, The sword and the stylus: An introduction to wisdom in the age of empires, Eerdmans, Grand Rapids. Rogerson, J.W., 2010, A Theology of the Old Testament: Cultural memory, communication, and being human, Fortress, Minneapolis. Seibert, E.A., 2009, Disturbing divine behavior: Troubling Old Testament images of God, Fortress, Minneapolis. Walton, J.H. & Hill, A.E., 2004, Old Testament today: A journey from original meaning to contemporary significance, Zondervan, Grand Rapids. Whybray, N., 2008, Job, Sheffield Phoenix, Sheffield. (Readings: A new Biblical Commentary).

1.Cf. Seibert 2009:15–34 for an overview of the problematic portrayals of God found in the Old Testament. For various defences of God’s disturbing behaviour, cf. Seibert 2009:69–88.2.There are of course beautiful descriptions of God’s love for his people found in the Old Testament as well. Cf. Hs 2:14 ff.; 11:1–11. 3.Cf. Nah 1:2, 8; 2:7; 3:3–6, 10, 15. 4.Cf. also Seibert 2009:116–117. Seibert argues convincingly that just because a text presents itself as historical does not mean that it is. He rightly points out that the reason why many Old

Testament stories seem historical to many people probably has more to do with their preconceived notions about these stories than with the stories themselves.

5.Cornelius 2009:249 points out that the number ‘seven’ indicates the ideal family. Cf. also Hartley 1988:68–69.6.Cf. Perdue 1994:130, 133 for a short description of this assembly, its constituents and its various functions, cf. also Balentine 2003:358; Cornelius 2009:251. 7.Cf. Cornelius 2009:251–252 for a short discussion of the meaning of the word ‘satan’, cf. also Goldingay 2006:54–55. Goldingay correctly points out that the word is not a name, but a

common noun. The satan is a member of Yahweh’s staff and he is responsible for bringing accusations against the righteous. Cf. also Clines 1989:19–22. 8.Kamp 2005:16 asserts that God’s consent to the satan’s proposal is prompted by inner pride. 9.For an exploration of the theme of death in the prologue of Job, cf. Mathewson 2006:36–64. 10.LaCocque 2011:21 understands God’s bet as a revelation of God’s vulnerability and his faith that a mere human would vindicate him. This viewpoint stands in contradiction to the position taken in this article. 11.Cf. Balentine 2003:359 who points out that this is the only case in the Hebrew Bible that the verbal construction

occurs in the Hif’il with the preposition

occurs in the Hif’il with the preposition

with God as the object of the verbal action. The verb means to stir someone into action that happened due to provocation. This reflects negatively on God’s nature, indicating that he can be coerced.

with God as the object of the verbal action. The verb means to stir someone into action that happened due to provocation. This reflects negatively on God’s nature, indicating that he can be coerced. 12.Cf. Clines 1989:48–49 for a discussion of the precise nature of Job’s illness. 13.Cf. Clines 1989:50 for an elaboration on this. 14.Cf. Clines 1989:50–54 for an in-depth discussion of the role of Job’s wife in the narrative. 15.In the words of Boss 2010:32, ‘the God of stability has become the God of destruction.

16.Rogerson 2010:167 writes that from a communicative point of view God’s reaction recalls the evasive answers that politicians are trained to give. Fretheim 2005:233–247 argues for the opposite viewpoint. He thinks that God’s speeches do provide an answer to Job’s misery and distress and that God takes responsibility for Job’s suffering through his creation and the sustaining of a world that is not risk-free, in which people do suffer undeservedly. The problem with Fretheim’s view is of course that Job’s suffering did not just happen, but that God Himself is responsible for it. Job’s agony and grief is not the result of a dangerous world filled with all kinds of risk, but the result of God’s wager with the satan. 17.Boss 2010:222 argues that due to his new and fuller understanding of God and himself, Job has encountered God now no longer as just his source, but as his destination. 18.Cf. Ngwa 2005:1. Ngwa’s study provides a comprehensive analysis of the text, the different versions of the text, the history of interpretation, and theological reflections on the epilogue. 19.These numbers are probably symbolic of wholeness and completion, cf. Mathewson 2006:166. 20.Cf. Hartley 1988:540; cf. also Brown 1999:235 who writes that God’s compassion is the motivation for his restoration of Job’s fortunes, cf. also Ngwa 2005:131–142 who suggests three possible meanings for the restoration of Job’s fortunes: firstly, the restoration can be understood as the response of God to the aspirations of servants who expect to be rewarded for their services; secondly, it can be read as a new beginning, where God and human unite to respond to the threat of evil in the world; thirdly, it can be understood as a reversal of chaos and the triumph of what is good. 21.Cf. Goldingay 2006:81–83 for a short discussion of Yahweh’s freedom. 22.Cf. also Walton & Hill 2004:3 who specifically refer to the Old Testament as God’s presentation of himself, as his self-revelation. 23.Seibert (2009:171–173) provides a number of reasons why this distinction between the actual God and the textual God is necessary. 24.To experience God as a living reality implies that God can be known. The existence of God cannot be scientifically proven and this statement should therefore be read as a confession of faith. Humans construct images of God, these constructs result from their own ideological-theological viewpoints. My own ideological viewpoint is that by faith God can be known as a living reality. 25.Cf. Gericke 2004:35–53 who presents seven arguments against the existence of Yahweh. Gericke goes beyond my own viewpoint, arguing that Yahweh as portrayed in the Old Testament is a character of fiction that does not exist outside the world of the text. My own viewpoint is of course that there is a textual God as well as an actual God.

|