|

Article Information

|

Author:

Andre van Rheede van Oudtshoorn1

Affiliation:

1Perth Bible College, Karinyup, Australia

Correspondence to:

Andre van Rheede van Oudtshoorn

Email:

andre@pbc.wa.edu.au

Postal address:

56 Lilburne Road, Duncraig 6023, WA

Dates:

Received: 21 Jan. 2011

Accepted: 12 July 2011

Published: 05 Oct. 2011

How to cite this article:

Van Rheede van Oudtshoorn, A., 2011, ‘Obeying God? Obeying Paul? Bridging the socio-cultural context in the interpretation of Biblical imperatives ’,

Verbum et Ecclesia 32(1), Art. #480, 7 pages.

doi:10.4102/ve.v32i1.480

Copyright Notice:

© 2011. The Authors. Licensee: AOSIS OpenJournals. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution License.

ISSN: 1609-9982 (print)

ISSN: 2074-7705 (online)

|

|

|

|

Obeying God? Obeying Paul? Bridging the socio-cultural context in the interpretation of Biblical imperatives

|

|

In This Original Research...

|

Open Access

|

• Abstract

• Introduction

• Biblical indicatives and the construction of a symbolic world

• The power of the imperatives

• A model for dealing with biblical imperatives

• Conclusion

• References

• Footnotes

|

|

When do we encounter God in the Pauline imperatives, or when is it Paul, the man of his times, that we are dealing with? This article develops a model to help

us determine the reach of the imperatives into our socio-cultural context today. The imperatives are shown to be more than ad hoc injunctions but, rather,

legitimate expressions of the new symbolic world in which both Paul and believers participate by faith. The imperatives carry an illocutionary force which relies

on such a shared symbolic world. By analysing Paul’s imperatives in terms of this symbolic world it is clear that he, at times, simply accepted the dominant

cultural interpretation of reality of his day at the cost of limiting the expression of his symbolic world. At other times he modified the dominant cultural

interpretation by calling believers to act contra-culturally in the light of the gospel’s new interpretation of reality. There are also instances where

Paul directly rejects certain aspects of the culture of the day in the light of the symbolic world. Paul’s flexibility to develop a variety of responses

towards the dominant culture of his day in the light of the indicatives of the gospel message provides an important key to developing a model to determine

‘if?’, ‘when?’ and ‘how?’, to apply the imperatives into our context today.

On a few diverse issues such as dress, hats and hair-styles churches have over the past few decades gradually come to accept the principle that the immediate

cultural context within which some Biblical imperatives were given radically limits the way in which they can be applied to our own situation today. By implication

the underlying hermeneutical principle that cultural context co-determines meaning has, thereby, been accepted. But just where do we draw the line to decide

which imperatives are to be seen as cultural-relative, and which retain absolute authority, allowing them to be applied directly to us today? In other words, on what

basis do we distinguish between one group of imperatives where we allow the cultural context to drastically limit their applicability to our world today, and others,

which we hold to be sacrosanct and untainted by their immediate cultural context? The question may be asked: when do we encounter God in the imperatives, or when is

it Paul, the man of his times that we are dealing with?

Many believers, it must be said, have remained uncomfortable with the idea that our interpretation of the Word of God should be limited in any way by the immediate

cultural context in which it was given. Feeding this negative attitude is the fear that eventually this approach must lead to a radical relativisation of all Scriptural

imperatives, even those which many see as core Biblical absolutes, particularly in the area of human sexuality and, for example, women in ministry.1

There does not seem to be any ‘simple’ model available to help pastors and lay people distinguish between those imperatives that remain directly applicable

to the context of today, and those that we can safely leave in their original context. Often the easiest way to bridge the cultural gap between ‘then’

and ‘now’ is to abstract general universal ‘principles’ from the imperatives and then apply these to today. As Colwell contests:

An honest acknowledgement of the contextual rootedness of biblical rules commonly issues in an attempt to identify principles of organising themes underlying those

rules, which can then be interpreted and reapplied as a means of responding to contemporary questions. (Ballard & Holmes 2006:214)

Colwell in Ballard and Holmes (2006:214) points out two major flaws with this method of generating principles. Firstly, he suggests, many of the original contextual

reconstructions using historical critical methods are, and remain, nothing more than fanciful conjectures. According to him, there simply is not enough evidence

available in most cases to accurately reconstruct the original context and, from this to identify the underlying principles that supposedly are reflected in the rules

and regulations. A second, and perhaps more serious, flaw which he points to is that ‘notions of justice, prudence, temperance are as contextually rooted as the

rules through which such notions are applied’ (Ballard & Holmes 2006:214). The Old Testament commandment not to commit adultery, for example, would probably

have been interpreted to refer to women and not to men. And if we consider this to be ‘unjust’ we must remember that the notion of justice meant something

else for people then, than they do for us now. Added to these important observations by Colwell one can add a third problem: imperatives that are turned into principles

always end up becoming more and more abstract and vague until they are finally resolved within large fuzzy concepts such as ‘love’ and ‘justice’

which are vague enough to accommodate any cultural definition of them. Karl Barth (1956) has reacted strongly against this way of dealing with imperatives:

We have poured the dictates and pronouncements of our own self-will into the empty containers of a formal moral concept, thus giving them the aspect and dignity of an

ethical claim (although, in fact, it is we who will them). (Barth 1956:664)

In order for the imperatives not to get lost in general principles, they need to maintain as much of their original force as possible to call believers to direct

obedient action. But how can this happen if the socio-cultural context within which they were originally meant to find expression has changed? In this article it will

be argued that the imperatives are legitimate expressions of a broader symbolic universe that is constructed from propositions and implications inherent in the gospel

message itself. This symbolic universe represents a new interpretation of reality in the light of the person and work of Christ who has inaugurated the Kingdom of God.

It will, further, be argued that the imperatives, even though they express the will of the risen Lord, carry an illocutionary (persuasive) force rather than coercive

power. This means that the dominant cultural interpretation of reality has to be taken seriously. The dominant culture is able to both challenge and limit the expression

of the new symbolic interpretation of reality. Paul’s imperatives, it will be shown, already express such a necessary accommodation to dominant culture. It will

be argued that by following the way in which Paul accommodated his imperatives to fit the dominant culture without denying the new symbolic world that his imperatives

were designed to express, we will be able to develop a model to help us deal with the way these same imperatives relate to our world.

|

Biblical indicatives and the construction of a symbolic world

|

|

According to Geertz, a symbolic world is a socially constructed set of shared meanings that form an ultimate definition and explanation of what ‘is’

(Geertz 1992:91–94). It is thus the presuppositions or the set of assumptions that we bring to any situation to help us make sense of it. Niebuhr suggests

that our actions are responses to the actions of others and that we decide which responses to make in the light of the interpretive community to which we belong:

‘Personal responsibility implies the continuity of a self with a relatively consistent scheme of interpretations of what it is reacting to’ (Niebuhr,

Gustafson & Schweiker 1999:65). The indicatives of the gospel construct the world and society in a new way. Belief in this new interpretation of reality calls

for the transformation of other cultural constructions of the world on both a cognitive and symbolic level. These symbols are expressed through practical day-to-day

actions which disclose the new understanding of the world:

We do not first believe certain things about God, Jesus, and the church, and subsequently derive ethical implications from these beliefs. Rather, our convictions

embody our morality; our beliefs are our actions. We Christians ought not to search for ‘behavioural implications’ of our beliefs. Our moral life is not

comprised of beliefs plus decisions; our moral life is the process in which our convictions form our character to be truthful. (Hauerwas 1983:16)

The imperatives and the indicatives of the gospel should be seen as two sides of the same coin. They cannot be separated from each other: ‘To reduce Paul’s

paranaesis to an afterthought is to misunderstand Paul’s theology. The imperative is the inevitable outworking of the indicative’ (Dunn 2006:630). If you

change the imperatives, you are changing the gospel from which they originate. In the same way, if you change the message you will have to develop new imperatives to

reflect the contents of that message. To quote Barth (1956) again:

The Word of God is both Gospel and Law. It is not Law by itself and independent of the Gospel. But it is not Gospel without Law ... It is first Gospel and then Law.

It is the Gospel which contains and encloses the Law as the ark of the covenant the tables of Sinai ... The one Word of God which is ... the Work of his grace is also

Law ... It is the claiming of his freedom. It regulates and judges the use that is made of this freedom ... The truth of the evangelical indicative means that the

full stop with which it concludes becomes and exclamation mark. It becomes an imperative. (Barth 1956:2511)

The message of the in-breaking of the Kingdom of God in and through the person and work of Jesus is counter-cultural, charged with the potential to radically challenge

our actions in this world by challenging society’s understanding of ‘how things are and work’. Our symbolic world, thus, forms the deepest

substructure for our actions in the world. Marxen (1993:206) illustrates this by pointing out that Paul’s injunctions to the Corinthian church challenged

their underlying understanding of humanity rather than simply their outward sexual behaviour. According to Marxen, the Corinthians argued from a dualistic view of

humanity that split body and soul, whilst Paul’s injunctions flowed from the Jewish understanding of the human as an intrinsic corporate unity. Paul’s

imperatives in this case were the result of a contra-cultural definition of reality and were aimed to both realise and sustain this new interpretation whilst

simultaneously challenging and deconstructing the Corinthian’s cultural understanding of what it means to be human.

The Pauline symbolic world is grounded on the person and work of Christ. Morna Hooker (Rowland, Tuckett & Morgan 2006:76) points out that whilst Christ is in

the foreground in the New Testament writings, God is in the background. It is exactly because the New Testament authors believed that God has acted in Christ, that

Christ is the central focus in the New Testament. Ridderbos shows that Paul uses the term ‘in Christ’ more than one hundred and fifty times in his

letters. The judgement on, and annihilation of, the old creation in Christ as well as the inauguration of the new creation in him, forms the basis of Paul’s

new interpretation of reality. The Pauline imperatives thus are perceived as authoritative because they are seen as emanating from the living Christ himself. It is

not Paul who issues these imperatives in his own name: they reflect the will of Christ, the Lord, himself. Fee (1996), commenting on 1 Corinthians 7, states:

Christ is always Paul’s ultimate authority. When he has no direct command, he still speak as one who is trustworthy (v. 25) because he has the Spirit of God

(v. 40) ... From his point of view his ethical instructions all come from the Lord. If he does not appeal more often to the sayings of Jesus themselves that

is because such teachings are the presuppositions of his own. The ‘ways’ of Jesus are lived out and taught in the ‘ways’ of the apostle.

Hence he feels no need for such an appeal. (Fee 1996:291)

The Lordship of Christ transcends the immediate cultural contexts; in confessing the Lordship of Christ the church everywhere and always recognises the right and

authority of Christ to rule everywhere: ‘That Christ delivers us from the present evil age and places a new creation (Gl 6:15) provides a cosmic framework for

the entire epistle’ (Polhill 1999:145). In the light of his Christological focus Paul redefines the world of the believers theologically (constructing a

new understanding of God)2, anthropologically (developing a new understanding or humanity according to faith), eschatologically (holding to a

new perspective on the future, and the present in the light of the future), ecclesiologically (redefining social relationship amongst believers and the world),

ontologically (constructing a new understanding how things ‘are’), epistemologically (recasting notions of the final truth), and

axiologically (what constitutes value or virtue), amongst others. Loubser (2007) points out:

the constraints of Pauline contextualisation ... never bypassed its Christological foundations (the solus Christus) but was the natural extension it. The Christ

event remained norma normans for Paul. To him it determined the present and the future of the believer in an absolute sense. Contemporary observers may ask:

how can Christ be conceived in such an absolute sense and yet be proclaimed in such a contingent mode? But this is a modern problem. Precisely because Christ was

absolute, Paul could proclaim him in such a contextual manner. (Loubser 2007:120)

Whilst Paul does not develop the theme of the Kingdom of God extensively, Ridderbos (1997) notes that this theme does play a significant role in the shaping of

Paul’s thought:

... the coming of the Kingdom as the fulfilling eschatological coming of God to the world is the great dynamic principle of Paul’s preaching, even though the

word ‘kingdom of heaven’ does not occupy a central place in it. That this deeper unity of the New Testament kerugma is once again being recognized in a

broad circle is among the great gains of the eschatological approach to Paul’s preaching as well. (Ridderbos 1997:44)

The concept of the Kingdom of God reaches beyond the domain of the church and has socio-cultural implications for the way believers are urged, called and commanded,

not only to interpret their world differently, but to restructure it according to the new rules of the Kingdom. These Kingdom rules are imperatives that call

believers to concrete obedience; to a critical examination and restructuring of their cultural context.

However, the imperatives of Paul, reflecting the will of the absolute Lord, do not always seem to have a direct relationship to the indicatives or the symbolic world

that define the Kingdom of God. An example is Galatians 3:28 where Paul states: ‘Faith in Christ Jesus have made each of you equal with each other, whether you

are a Jew or a Greek, a slave or a free person, a man or a woman’. In contrast to this statement of equality, Paul’s concrete imperatives still allow for

unequal relationships such as masters and slaves, and the submission of the wife to her husband. This poses the questions: what kind of power do the imperatives

represent and, secondly, why is there this gap between the ‘ideal’ and the imperatives through which this ideal is supposed to be expressed in the

praxis?

The power of the imperatives

Galatians 3:28 provides an excellent entry point to examine the kind of power or force that is reflected in the imperatives. Habermas has indicated that illocutionary

force or persuasive power is only possible within an ‘ideal communication situation’ where, amongst other things, people meet each other as equals and are

not compelled by any external force (such as a gun to their heads) to submit to a particular position (Loubser 2007:120; see also Goode 2005:66). This ideal

communication situation seems to be reflected in Galatians 3:28 but then within the context of the Lordship of Christ. It may be argued that the idea of Christ as

Lord, the absolute King with obedient subjects, who stands as the force behind the imperatives contradicts any notion of true equality. Without such equality,

Habermas contends, there is only raw power, not an illocutionary force. This argument can be countered in three ways.

Firstly, the nature of the Kingdom of God that has been realised in Christ needs to taken seriously. The Kingdom does not come by external force, compelling those

belonging to it to obey the commands. As we have already shown, the imperatives function in the context of the indicatives, which speak of the love of God that

overcomes the world by God emptying himself, becoming fully human and then, in Christ’s love, dying for it. The

Word, who commands the church, also encounters the world in humility and vulnerability. Moltmann (2001) has shown that the resurrected King

of glory is and remains the rejected crucified one:

So we must subject belief in the resurrection to the history of the crucified Christ as its true criticism ... For he who was crucified represents the fundamental

and total crucifixion of all religion: the deification of the human heart ... the worship of those with political power, and their power politics.

(Moltmann 2001:33 & 165)

Secondly, the Lord does not speak directly to the church, but indirectly; the imperatives come through Paul, who has no power other than the power of the message

that refers to the crucified Christ. It is the crucified Lord that informs his reasoning. Paul, himself, had to face opposition and had to battle to ‘take

captive every thought to make it obedient to Christ’ (2 Cor 10:5). Paul’s injunctions may be tested against the message to see if they truthfully

represent the implications of the message. One can say that the imperatives have authority and power because they are Christ’s commands issued through

Paul; at the same time, they only exert an illocutionary force because they are Christ’s commands through Paul.

In the third place, the imperatives are not primarily underpinned by threats but by the good news about what God has done for the world in Christ and the promise

of the final realisation of this new reality in the coming Kingdom. Promises are ‘performative’, because they ‘constitute the performance by the

speaker of the speech act with the illocutionary force named by the performative verb’ (Vanderveken 1990:18). The promise of God, grounded on the covenant and

his acts in history in Jesus, represents a ‘direction of fit’ in which the words of the promise become the controlling test as to whether reality has

indeed been transfomed in line with the reality envisioned in the promise (see Lundin, Thiselton & Walhout 1999:239). Moltmann (2002) stresses the link between

the imperatives and God’s promise and concludes:

The imperative of the Pauline call to obedience is accordingly not to be understood merely as a summons to demonstrate the indicative of the new being in Christ,

but it has also its eschatological presupposition in the future that has been promised and is to be expected – the coming of the Lord to judge and reign.

Hence it ought not to be rendered merely by saying: ‘Become what you are!’, but emphatically also by saying: Become what you will be!’ (Moltmann

2002:148)

These three arguments all show that the imperatives carry an illocutionary force rather than raw power. They do not compel, they persuade. Their persuasive power,

in turn, is linked to the message about the Kingdom of God inaugurated in and through Christ.

The second question that we need to consider concerns the seeming disjunction between the indicatives and the imperatives that we encounter in Paul. The statement on

social equality given in Galatians 3:28, whilst pronounced within a specific context to a particular church, clearly also has the power, by implication, to call

society as a whole into question. It does this by challenging some of the foundational presuppositions according to which society in Paul’s day was structured.

Francis Esler has shown how much of Paul’s writing is about constructing a new identity for Christians and with that a new social order (Esler 2003). The

problem, as we have indicated, is that Paul does not seem to express this new social order that is supposed to mark the identity of Christians in his imperatives

to the church. There, it seems, inequality is fully accepted. This gap, however, is not, in the first place, between the indicatives and the imperatives. It is,

rather, between two sets of indicatives; those which inform the Christian’s symbolic world and those which inform the dominant culture’s interpretation

of reality. The Christian participates by faith and hope in both realities. Faith allows the believers to already participate in the new creation despite his or her

continued participation in the old; hope sets him or her towards the realisation of the new within with the old in the expectation of its full realisation with the

coming of Christ (see McGrath 2006:670):

The theme of ethics is this ‘walking between two worlds.’ It is in the strict sense the theme of a ‘wayfarers’ theology,’ a theologia

viatorum. It lives under the law of the ‘not yet’ but within the peace of the ‘I am coming soon’ (Rev. 22:20). Theological ethics is

eschatological or it is nothing. (Thielicke 1966:47)

The imperatives are directed towards the church, the world of believers, and not the world of unbelief. The church cannot directly change the unbelieving world. It

cannot legislate the new norms of the Kingdom of God within this world, for to do so would divorce the imperatives from the indicatives of the gospel which call for

faith in Christ and love for God and others, as their deepest motivation:

Indicative and imperative are logically connected in the way that the indicative spells out the content itself of the state in which Christ-believers already find

themselves, a content that the paranaesis then urges them to actualize or show in practice. Thus the paranaesis logically presupposes the indicative and the latter

is logically directed towards the former. (Engberg-Pedersen 2000:8)

The Biblical imperatives should be understood as the minimum cultural transformation within a given context that the kingdom rule of Christ requires from those

who claim to believe the message of the gospel in order to reflect an alternative interpretation of reality to that of the dominant culture. Dunn (2006:630) states it

well: ‘Compromise (Paul would probably have preferred to say principled compromise) is an unavoidable feature of ethical decisions for those living between

the ages’. That the church is called to enact only the maximum cultural transformation possible allows it to remain relevant in a variety of cultural

contexts. This is illustrated in the minimal commands imposed on gentile converts by the church in Jerusalem (Ac 15). The Jerusalem church had to take the immediate

cultural context of the gentiles so seriously that it had to accept the limitations that the culture of the gentiles imposed on its own world view founded on the old

covenant faith (see Houlden 2004:60). Paul’s insistence that the gentiles did not have to abandon their culture to first become good Jews before becoming good

Christians, still holds true for our relationship with the culture of our day:

So much within culture is mundane. Merely living that is amoral, redundant and reflective. It is surviving in contexts impacted by economic, social and political

structures that are constantly changing. God affirms humans in the midst of their survival. (Shaw & Engen 2003:215)

Yet, at the same time, this call for the church to accept the limitations that the world imposes on it, does not relieve the church of its responsibility to radically

challenge the existing status quo in the light of the new symbolic world that it proclaims. The cross of Christ continues to stand as the ultimate critique of all

dominant world-views:

The recollection of the crucified Christ obliges Christian faith permanently to distinguish itself from its own religious and secular forms. In Western civilization,

this means, in concrete terms, distinguishing itself from the ‘Christian-bourgeois world’ and from Christianity as the ‘religion of contemporary

society’. (Moltmann 2001:34)

In considering slavery, for instance, we can say that Paul had to accept the phenomenon of slavery as a reality of the cultural context in which the church existed

(see Loubser 2007:196–204): ‘Paul lived in a group-oriented culture in which acceptance by the larger community was imperative’ (Polhill 1999:155).

This is in sharp contrast to Paul’s symbolic world in which he believed that, in Christ, the distinction between master and slave had already been abolished.

Does this mean that Paul had ‘sold out’ to the culture of his day? Note, however, that Paul also acted to limit the use and abuse of slavery within the

context of the church. Flowing from his symbolic world-view Paul could go so far as to use subtle theological and sociological pressures to challenge Philemon, a

Christian leader, to free his slave, Onesimus, who had also become a Christian. In this particular case, Paul declares that he had deliberately refrained from using

his power and authority in the church to demand obedience, even though it was his right to do so, in order to first bring Philemon to embrace the same symbolic

world-view as himself. Only a new understanding of reality, a radical transformation of Philemon’s way of thinking, had the power to foster a deep and continuing

transformation of his life and actions in the world. As Fager (1993) states:

Once a universe is understood it is possible to live in it because there is a continuity between the descriptive (what is) and the normative (what ought to be) in

universe construction and maintenance. (Fager 1993:19)

We have thus far argued that Biblical imperatives flow from a symbolic universe constructed according to the indicatives of the gospel. The Biblical imperatives

invite believers to a ‘gestalt switch’, to act in accordance to their Christian definition of reality rather than their cultural paradigm. The church,

however, remains grounded in its immediate cultural context and can only construct and live within a limited alternative interpretation of reality as a sign to the

world. The Biblical imperatives carry an illocutionary force which calls the church to retain its commitment to the alternative symbolic world of the gospel through

faith and to also to hope for the new creation to finally break through in this world. The church realises that it can only put up signs of the coming transformation

of the world through the proclamation of the gospel, and not by its actions alone. This means that the church can never act as a political entity. If it legislates

behaviour appropriate to the gospel, it denies the very essence of the gospel. The imperatives flow from the Lordship of Christ, who rules through the domain of

persuasive love, and always point back to him.

From these reflections we will endeavour to construct a model for bridging the gap between ‘then’ and ‘now’ for the Biblical imperatives.

Malina (Int. 36, p. 233–240) indicates that there are three basic models underlying different definitions of the social-cultural world. Firstly, the

structural functionalist model which understands society as static system in which different elements all work to maintain the given system. Any

deviation from the generally accepted world-view is seen as a threat and resisted. In contrast to this, Stuart Hall (1992) propounds a conflict model of

society in which the cultural status quo is seen as resulting from a continues battle for ideological dominance amongst different ideological groupings and in which

the stronger groups force the others into subjection. Texts function as ideological tools to support or undermine the dominant culture. The more the text can be used

as a relevant ideological tool in the ideological battle for broader cultural dominance, the more the text will grow in stature. The third model to depict the social

cultural world is the symbolic model which sees society as providing a foundational interpretation of the reality through symbolic meanings that are attached

to valued objects.

All three these models of culture can play a part in helping us understand how the Biblical imperatives interact with culture. Believers remain part of society and

thus participate in maintaining their own culture (model 1). At the same time they are called upon to challenge their culture in the light of their new definition of

reality constructed from the Biblical message (model 2). In line with model 3, believers are called to transform their world on a deep symbolic level through the

construction and practical implementation of a new way of thinking that finds expression in actions.

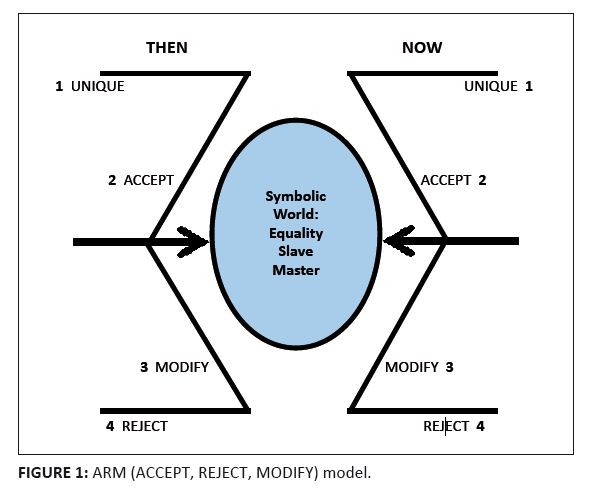

A model for dealing with biblical imperatives

The model proposed in this article starts by considering the way in which Paul engaged with the culture of his day. From this a mirror image is created for the

church to emulate within different cultural contexts. The key terms of the model are ACCEPT, REJECT, MODIFY (ARM) and TRANSFORM. From these operational terms some

basic interpretive rules can be formulated:

• Paul’s acceptance of his culture forces a modification of the Christian symbolic universe on him – this modification is marked by hope for the

final and full transformation of the old reality in subjection to the new. As Paul accepted his culture, even where it militated against the new reality in

Christ, we should accept our dominant culture in the hope of its ultimate transformation.

• The elements which Paul rejected in his culture as being contrary to the new interpretation of reality according to the gospel, should also be rejected

by the church of today.

• The places where Paul endeavoured to modify the harsher elements of his culture in accordance with the gospel’s reconstruction of reality should be

mirrored by the church of today – even though the ideologies to be modified may be radically different from those that Paul had to deal with.

• There are obviously also some imperatives that are so bound to the immediate context that they fall outside the scope of any model that wishes to make them

relevant to today.

• Transformation can only happen on the basis of the new symbolic universe constructed from the indicatives of the gospel under the Lordship of Christ in which

believers participate in love and hope.

Let us now consider the model more closely.

Number 1 refers to certain events which are unique to the original communication situation in the Biblical text (Paul’s admonition for Timothy to bring

his coat, for instance). Such imperatives remain unique in that they do not carry an illocutionary force in line with the symbolic world. When it comes to our world,

we need to also recognise that there are many issues which are unique to the modern day situation and that, therefore, cannot be addressed directly by reference to

particular contextually given imperatives. Our culture and its issues now remain distinct from the culture then with its issues. We can only deal with

these unique issues in our culture via Paul’s indicatives and the symbolic world that straddles both the believers’ world then and our world

now. We are required to find unique imperatives for the problems of today that will allow the symbolic world of the Bible to effectively confront and transform

our world.

|

FIGURE 1: ARM (ACCEPT, REJECT, MODIFY) model.

|

|

Number 2 indicates that Paul accepted the culture of his day. The structures of slavery as well as a male-dominated society, for instance, were both recognised

and accepted by Paul as supra-personal, ideological cultural dimensions within which the church had to function. In the same way, the church, today, also has to

function within similar supra-personal cultural ideologies and structures. This model calls on us to accept the culture of our day in the same way as Paul accepted

his culture. Western Christians, for instance, live within the context of ideologies such as (post-) modernism, secularism, individualism and capitalism. We can say

that that is just the way in which our world works and it is impossible for the church or individual Christians to think that that they can live completely outside of,

or in opposition to all of these interpretations of reality and still remain relevant to their culture. According to this model, we should argue that as much as Paul

accepted the cultural roles given to men or women in his day, we too must accept the roles given to men and women within our society – even if our culture and

the culture within which Paul functioned, directly oppose each other. This means that, in the same way that the church had to operate within a culture where it was

deemed unacceptable for women to speak in public, so the church must now accept and live within a context in which it is unacceptable for women to be excluded from

public speaking. The intention behind Paul’s acceptance was for the church to function within the culture of his day. Believers did not have to first accept a

different (i.e. Jewish) culture in order to be Christians – they had to accept their given world or culture and learn to live as Christians within it.

Number 3 indicates that Paul did not blindly accept everything which his culture demanded but limited this acceptance, charging the believers to modify their

behaviour on some key issues. Whilst accepting the structure of slavery, for instance, Paul immediately limited the way in which slaves were to be treated and the

way they, in turn, were to treat their masters. In the same way, the status of women in the Christian church was not seen as being lower than men in general –

they were called upon to submit3 to their own husbands, rather than to be subservient to men in general. And even this submission was placed in the

broad context of mutual Christian submission to each other. Furthermore, men were called upon to love their wives, just as Christ loved the church. According to our

model, then, modern day Christians are called to apply the same modifications that Paul had made to his culture to their own culture. This implies that we cannot

blindly follow the secular capitalistic ideology of the culture within which we live; Christian managers still need to reckon with the fact that God, and not money,

is their final master and treat their employees accordingly.

Number 4 points out that Paul not only accepted and modified the culture of his day, but that he also deliberately rejected some elements within the culture

as being ‘unworthy’ of Christian conduct. In this regard we can think of issues such as drunkenness, prostitution or homosexuality. In most cases, such

rejections pertain to individual conduct; that is, conduct that falls outside of the supra-personal structure of society, but which, rather, demands a personal

decision from the believers within a particular society. According to this model, aspects in our current society, which Paul had already rejected, as ‘under

the wrath of God’ or ‘unworthy of the Lord’, also need to be radically rejected by us and individual believers are still called to turn from such

‘worldly’ behaviour.

Number 5 indicates that the symbolic universe that Paul operates from is linked to the indicatives of the gospel message that transcend and also radically challenge

the given culture – both then and now. The symbolic universe challenged the culture in Paul’s time; angels and demons, for instance, lost their places of

power in the light of the victory of Christ. People were seen as radically equal before God and each other. In the same way, according to this model, our modernistic

ideology that disallow any super-natural powers, can and should be challenged by the symbolic world of the Bible. And similarly, our structures of economic inequality

should be challenged by the fact that we all are equal before God.

The imperatives functioned as a practical challenge to the faith of the believers and the world in which they had to live. In the same way the imperatives must also

function as a practical challenge to our own socio-cultural definition of reality. Our obedience is the sign that we believe in the new interpretation of reality in

the light of Christ. Only when the imperatives function as a natural outflow of this new interpretation of reality will they retain their power and existential urgency.

In this article we have considered how the immediate cultural context played a role in shaping the injunctions which Paul gave to the first believers and how it

may still play a role in our life-world. The imperatives were shown to carry an illocutionary force, even though they operate within the context of the Lordship

of Christ. We have also considered the need to accept the dominant culture, whilst seeking ways to modify it in order to reflect the new interpretation of reality

that operates within the church. Other elements within our culture need to be rejected because they militate against the symbolic world view generated by the

indicatives of the message. All this is with the view to the on-going transformation of reality through the call to faith that result in obedience. It became

clear that Paul utilised all of these elements in his injunctions. We are called to do the same – even maintaining some cultural elements which differ

radically from the cultural context which prevailed at the time of Paul’s writings. The Biblical imperatives presuppose the world as a way of being and

call us to live out of a new definition of reality based on the person and work of Christ. Without linking the Biblical imperatives to the indicatives of the

message we will only change society on the surface level and end up with legalism and casuistry. The ARM model helps us to find a rational framework for

transposing the imperatives into our world in order to attain the same counter-cultural effect to put up signs of the Kingdom of love that has broken into

this world in Jesus.

Ballard, P.H. & Holmes, S.R., 2006, The Bible in pastoral practice: Readings in the place and function of Scripture in the church, William B.

Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rapids, MI.

Barth, K., 1956, Church dogmatics: The doctrine of the word of God. 2 pts, T. & T. Clark, Edinburgh, UK.

Dunn, J.D.G., 2006, The theology of Paul the Apostle, William B. Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rapids, MI.

Engberg-Pedersen, T., 2000, Paul and the Stoics, Westminster John Knox Press, Louisville, KY.

Esler, P.F., 2003, Conflict and identity in Romans: The social setting of Paul’s letter, Fortress Press, Augsberg, MN.

Fager, J.A., 1993, Land tenure and the biblical jubilee: Uncovering Hebrew ethics through the sociology of knowledge, Continuum International Publishing

Group, New York, NY.

Fee, G.D., 1996, The first epistle to the Corinthians, William B. Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rapids, MI.

Geertz, C., 1992, The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays, Basic Books, New York, NY.

Goode, L., 2005, Jürgen Habermas: Democracy and the public sphere, Pluto Press, London, UK.

Hall, S., 1992, Culture, media, language: Working papers in cultural studies, 1972–79, Routledge, London, UK.

Hauerwas, S., 1983, The peaceable kingdom: A primer in Christian ethics, University of Notre Dame Press, Notre Dame, IN.

Houlden, J.L., 2004, Ethics and the New Testament, Continuum International Publishing Group, New York, NY.

Loubser, J.A., 2007, Oral and manuscript culture in the Bible: Studies on the media texture of the New Testament, explorative hermeneutics, African

Sun Media, Stellenbosch.

Lundin, R., Thiselton, A.C. & Walhout, C., 1999, The promise of hermeneutics, William B. Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rapids, MI.

Marxsen, W., 1993, New Testament foundations for Christian ethics, Fortress Press, Augsberg, MN.

McGrath, A.E. (ed.), 2006, The Christian theology reader, Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, Malden, MA.

Moltmann, J., 2001, The crucified God: The cross of Christ as the foundation and criticism of Christian theology, SCM, London, UK.

Moltmann, J., 2002, Theology of hope: On the ground and the implications of a Christian eschatology, SCM, London, UK.

Niebuhr, H.R., Gustafson, J.M. & Schweiker, W., 1999, The responsible self: An essay in Christian moral philosophy, Westminster John Knox Press,

Louisville, KY.

Polhill, J.B., 1999, Paul and his letters, B. & H. Publishing Group, Nashville, TN.

Ridderbos, H.N., 1997, Paul: An outline of his theology, William B. Eerdmans Publishing, Grand Rapids, MI.

Rowland, C., Tuckett, C.M. & Morgan, D., 2006, The nature of New Testament theology: Essays in honour of Robert Morgan, Wiley-Blackwell Publishing,

Malden, MA.

Shaw, R.D. & Van Engen, C.E., 2003, Communicating God’s Word in a complex world: God’s truth or hocus pocus?, Rowman & Littlefield,

Lanham, MD.

Thielicke, H., 1966, Theological ethics, Fortress Press, Augsberg, MN.

Vanderveken, D., 1990, Meaning and speech acts: Principles of language use, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK.

|

|