|

In this article, we described how gender is represented on two Christian book covers by popular author, John Eldredge, namely

Wild at Heart. Discovering the Secret to a Man’s Soul (2001) and Captivating. Unveiling the Mystery

of a Woman’s Soul (2005). Through semiotic visual analysis, we explored how the active male–passive female

opposition functions on these covers. This opposition is constructed by visually associating the male figure on the cover of

Wild at Heart with active outdoor adventurism and the female figure on Captivating with passive situatedness in

nature. The titles of the two books also contribute to positioning the male as active and the female as passive. We further

investigated how certain myths are created on these covers in support of an active male–passive female opposition and

its underlying ideologies. The cover of Wild at Heart creates and also taps into the colonial myth of conquest. The cover

of Captivating creates and taps into the myth of the fairytale and visually represents the female figure in a whimsical

manner, thus constructing her as a representation of the spiritual or divine. The article questioned the role this information

design plays in prescribing the expectations of gendered identity.

In 2001, pop-psychology best-selling Christian author, John Eldredge, published his answer to what secular and Christian theorists

alike had deemed a crisis in Western masculine identity. The book, Wild at Heart. Discovering the Secret to a Man’s Soul,

instantly became a best-seller with about 3 million copies sold world-wide (Hagenau 2009). The book has been translated into 16 languages

and made the Publisher’s Weekly best-seller list for four consecutive years. Writer for the popular Christian magazine,

Christianity Today, Douglas LeBlanc (2004:34) states that, ‘Eldredge… [is] leading a small revolution in Christian

spirituality.’1 John Eldredge, born 06 June 1960, is an author, counsellor and lecturer who, after a brief encounter with Eastern mysticism, Lao-Tzu and

New Age spirituality, became a Christian. He was apparently inspired by the writings of the renowned Swiss apologist, Francis Schaeffer,

whose philosophical musings led Eldredge to commit himself to the Christian faith. So compelled was Eldredge by Christianity, that he

eventually got a master’s degree in counselling and practiced as a Christian counsellor in Colorado Springs before working for

Focus on the Family, the American evangelical nonprofit organisation founded in 1977 by James Dobson. In July 2000, Eldredge left Focus

on the Family to launch Ransomed Heart Ministries, a ministry devoted to furthering what he termed the sacred romance between God and man,

a relationship apparently ‘lost and shrouded by religion’ (Ransomed Heart Ministries 2009:1 of 2). Since then John Eldredge

(as well as his wife, Stasi Eldredge) has become fuel for the recent flame of what might be termed pop-Christianity or the on-going

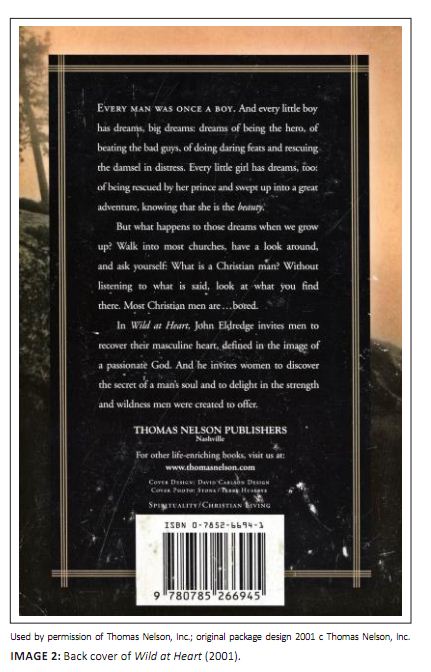

commercialisation of faith. Wild at Heart primarily centres on the invitation that Eldredge extends to all Christian men to ‘recover their masculine

heart, defined in the image of a passionate God’ (from the back cover, see image 2). In other words, it addresses the role of

masculinity in contemporary evangelical Christian culture. In spite of harsh criticism from many who felt uncomfortable with Eldredge’s

easy reductionism and determined essentialism he joined forces with his wife to, in 2005, bring out a companion version to

Wild at Heart entitled, Captivating. Unveiling the Mystery of a Woman’s Soul. As the title suggests, this book concerns

the captivating quality or nature of the feminine. It is difficult to explain the basic premises of these books without creating a straw man,

but one might say that Eldredge attempts to ‘discover the secret of a man [or woman’s] soul’ as proffered by the subtitle

to Wild at Heart. Simply put, Eldredge (on the back cover of Wild at Heart) suggests that the secret to a man’s soul is

that he desires a battle to fight and the secret to a woman’s soul is that she desires to be desirable. Simple as that. This article is concerned with the Eldredges’ propensity to exaggerate and hype gendered notions of ‘calling’ or

universal purpose. Critical reviewer, Colleen Carrol Campbell (2007:51), states that ‘the Eldredges devote most of their book

[Captivating] to explaining and defending intrinsic differences between the sexes …’. Specifically, we would like

to address the covers of the two books in question, namely Wild at Heart and Captivating. The case of these covers is

relevant, because not much is available in academic literature about Wild at Heart and even less about Captivating.

2 No critique or reading of these covers appears in the literature dealing with the books and it is this gap in available

research which this article seeks to fill. Despite the fact that these books were published in 2001 and 2005, they still spark debate and receive reviews even in 2010.

The books’ longevity in terms of eliciting

critical attention, as well as the prolific sales figures they have reached internationally, justifies an investigation of this

nature. Susan Hagenau (2009), brand manager for Thomas Nelson, publisher of Wild at Heart and Captivating,

confidently declares that both books ‘are still selling well’. Indeed, both books remain to date an unavoidable

presence on the contemporary Christian literary landscape.

The visuality of Christian culture is worthy of analysis, not least because Christian visual media must influence Christian culture and

not just the other way around. For this reason, the manner in which beliefs about gendered sex roles are communicated through the visual

material promoting itself as ‘Christian’ in the hegemonic sense demands analysis from a secular (feminist) perspective. As

early as 1935, Walter Benjamin, famously reflected on the feeling of strangeness that overcomes the actor before the camera and that this

sense of estrangement is akin to that felt by anybody looking into the (now Lacanian) mirror. Benjamin (1935:9) mooted that through

technology the reflected image has become separable, transportable. In answer to the question of where this image is transported, he

comments, ‘Before the public’ (Benjamin 1935:9). The image reflected back to the viewer from a book cover is surely no

different. It is a code that speaks to the viewer about their own identity and suggests to them how this may be performed in the public sphere. According to Stuart Hall’s (1980) encoding/decoding communication model various phases or ‘moments’ can be identified in

the process of communication. Chandler (1994) draws our attention to the fact that further elaboration on these ‘moments’ can

be found in John Corner’s (1983) three definitions of the phases of encoding and decoding. The first phase is the encoding phase or

the moment of writing. According to Corner (1983:266), this first phase is informed by ‘the institutional and organizational practices

of production, governed by media policies and by the professional and medium-related conventions of language and image use.’ The second

phase is identified as ‘the moment of the “text” itself’ and is, for Corner (1983:267), ‘the particular

symbolic construction, arrangement and perhaps performance which is the product of media skills and technical and cultural practices.

’ The moment of the test represents the form and content of the communication. Finally, the third phase, the moment of decoding

is defined as the moment of reception or consumption of communication by readers, viewers or any audiences, who actively decode messages

as opposed to merely passively receiving them. According to Corner 1983:267) this phase entails ‘the practices by which the reader

/hearer/viewer, drawing on the particular linguistic and cultural competencies available and apparently appropriate, “makes sense”

of, and realizes into coherent meaning’ the communication, its form and its message. According to Chandler (Chandler 1994), Hall

(1980:128) also makes reference to various ‘linked but distinctive moments - production, circulation, distribution/consumption,

reproduction’, which form part of what Hall theorises as the communication circuit. We are concerned with the encoding and decoding of the semiotic images used in the design of the two book covers, but hope to treat these

as fluid and acquiescent within our hypothetical matrix of meaning. It is our belief that visual representation is a means of revealing

constructs of identity in terms of their performativity and we hope to demonstrate this through our discussion of the images used to sell

these books. Publishers, editors and media theorists alike agree that the cover art on books is imperative in procuring those all-important impulse buys.

Malcolm Muggeridge famously proclaimed the Time cover spot as ‘post-Christendom’s most notable stain-glassed window’,

indicating that in the media-scape of impetuous consumerism, covers communicate the ideological brand of the author. For those of us researching

visual media, book covers implicate the author in a semiotic language or dialect that betrays his or her commitment to a certain set of visual

ideologies or tropes. Within gender studies, book covers may be seen as referents to the gendered ideals of the author just as glossy men’s

magazine covers, for instance, project the objectifying ‘body fascism’ (Nead 1992) that is the mainstay of these publications.

Book covers are, thus, as important as codes of visual ideology as magazine covers and require critical problematising and demystifying.

In that vein, we hope to analyse the covers of both Wild at Heart and Captivating. It is noteworthy, that the covers have never changed since they were first published, indicating that the authors and publishers feel content

with the manner in which the cover art represented the contents or ‘message’ of the books. Hagenau (2009) describes the creative

process around these covers as follows: As far as the imagery on the covers, the designers read the manuscript and covers are created from the imagery that comes to mind when

reading and what appeals to the author and his audience. (Hagenau 2009) As, mentioned before, the publishers feel that the books are still selling well and that there is thus no need for redesign of the covers or

re-branding of the books (Hagenau 2009). The covers of Wild at Heart and Captivating have, therefore, to some degree become

iconic of the Eldredges’ ideas regarding what it means to be either a man or a woman in Christian culture. The primary fault that theorists and bloggers alike seem to find with both texts is the shaky theology employed by the Eldredges3.

It seems fair to say the argument of either book is supported by popular media myths and fairytales rather than theological discourse.

The books are also frequently criticised for their simplistic view on gender roles. Authors Sally Gallagher and Sabrina Wood (2005:157)

state that; ‘[Wild at Heart] places a non-negotiable and dimorphous gender identity at the centre of the story.’

Similarly, Brynn Camery-Hoggatt and Nelson Munn (2005:24) note that, ‘Eldredge’s gender stereotypes present masculinity and

femininity in a way that is incomplete, culturally dictated, and old-fashioned.’ Based on the previous discussion, this article has the following aims: Firstly, to describe how the Eldredges’ ideas translate

into visual terms. Secondly, to describe how gender is represented on these covers and how the covers construct gendered Christian identity

and thirdly, to investigate whether the covers participate in the propagation of gendered stereotypes found in mainstream, Christian culture.

In order to address the above aims we employed an integrated semiotic analysis and discussion of the two book covers from within a Barthesian

tradition, based on a description of connotations of signs, the construction of mythic meaning, as well as created and supported ideologies

(Barthes 1972 & 1979). Specific denotative descriptions of the signs present on these covers are, where they are not discussed in

conjunction with connotative meaning, generally omitted for the sake of remaining concise. We adhered to a basic Barthesian semiotic analysis, focusing on how meaning is constructed through signs and their various combinations,

the connotations these hold from our social experiences and the way in which ‘[m]yth takes hold of an existing sign and makes it

function as a signifier on another level’ (Bignell 2002:17). Myth, in Barthes’ (1972:129) terms, makes socially and culturally

determined and constructed messages appear common-sense and natural. Myth is thus a distortion of reality, but nevertheless hides nothing,

as its function is to obscure (Barthes 1972:121). Barthes (1972:109) also declares that: ‘Myth is a type of speech’. In our

subsequent analysis, we considered how the two covers construct meaning and produce their own mythic language or way of talking about

Christian gender. We also explored the ideological implications thereof.

Wild at Heart

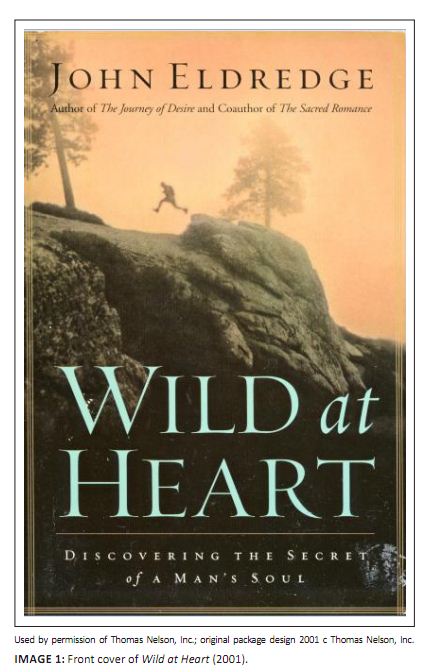

‘The stallions hang out in bars; the geldings hang out in church’ (David Murrow, as quoted in O’Brien 2008:49).The front cover of Wild at Heart (Image 1) shows a man in silhouette jumping from an elevated rock to a plateau that appears

to be at the summit of a mountain. On either side of him are tall fir trees that create vertical drama within an otherwise tranquil

scene. It appears to be either sunrise or sunset. Eldredge’s name appears as a banner above the sprinting silhouette with the

titles of his other best-sellers written beneath his name. On the bottom half of the cover Wild at Heart is written in an

oversized, pale blue font that is in high contrast with the dark mountainside that forms the backdrop to the title and subtitle.

A somewhat old-fashioned, stoic, seriffed

typeface is used for all the copy that appears on the cover, possibly connoting traditional masculine associations of stability,

logic and boldness.

|

IMAGE 1: Front cover of Wild at Heart (2001).

|

|

We cannot hope to give a definitive meaning for this design, but may attempt to situate the cover art within the context of the book

and Eldredge’s broader thesis in an effort to surmise potential readings of the image on the cover as a means of understanding

one of many possible gender constructions within Christianity as a visual trope. The first question, then, is what Eldredge seems to

be saying about Christian masculinity with this book. The book’s credo is spelt out as the following, ‘in the heart of every

man is a desperate desire for a battle to fight, an adventure to live, and a beauty to rescue’ (Eldredge 2001:9). Early on in the discussion, Eldredge (2001:41) quotes Henry David Thoreau as musing, more than 150 years ago, that: ‘The mass of

men lead lives of quiet desperation.’4 To Eldredge this appears to be the great truth of the current age, which men

everywhere in the Western world are in a state of crisis. He is not the first to suggest this. In 1978 the celebrated Christian author,

Leanne Payne, wrote a book entitled Crisis in masculinity and in 2000 the secular theorist, Anthony Clare, entitled his psychological

analysis of contemporary men, On men: Masculinity in crisis. But Eldredge was, perhaps, the first writer to popularise this idea.

The problem, according to Eldredge (2001:41–42), is that ‘there is no battle to fight, unless it’s traffic and meetings

and hassles and bills’ … all of which lead to anger and boredom rather than a sense of really being alive. In the typical

language of mythic popular culture, Eldredge quotes the filmic William Wallace who in Braveheart (Gibson 1995) sagely mused that

‘all men die, few men live’. Through the early chapters of the book it becomes clear that for Eldredge every boy and man

questions whether he has what it takes. Whether he, like William Wallace, could fight the foe and win the girl. Eldredge seems to feel

that contemporary Western men have lost their ability to fight for what they believe in, they have lost their masculine essence.

And that, according to Eldredge (2001:48), is the problem, that most men are not ready ‘to fight, to live with risk, to capture

the beauty.’ This so-called problem is apparently aggravated by the church.

|

IMAGE 2: Back cover of Wild at Heart (2001).

|

|

Wild at Heart sowed seeds that, according to Brandon O’Brien (2008:49) sprouted as a new masculinity movement aimed to

get men into church by changing the church’s atmosphere. In South Africa, we are experiencing a further religious (gendered)

wave in the Mighty Men phenomenon spear-headed by potato farmer, Angus Buchan, a movement that seemingly attempts to re-align men with

a godly vision of masculine identity (and responsibility?). David Murrow, author of Why men hate going to church (2005),

founded the group Church for Men in the United States because, whilst the local congregation is ‘perfectly designed to reach

women and older folks’, with its emphasis on comfort, nurture and relationship, it ‘offers little to stir the masculine

heart, so men find it dull and irrelevant’ (in O’Brien 2008:49). In Driscoll’s opinion, the church has produced

‘a bunch of nice, soft, tender, chickified church boys’ (in O’Brien 2008:49). In his oafish, bombastic and homophobic

way, Driscoll goes on to maintain that ‘latte-sipping Cabriolet drivers’ do not represent biblical masculinity, because ‘

real men’ (like Jesus, Paul and John the Baptist) are ‘dudes: heterosexual, win-a-fight, punch-you-in-the-nose dudes’

(in O’Brien 2008:50). In other words, because Jesus is not a ‘limp-wristed, dress-wearing hippie’5 (Driscoll

in O’Brien 2008:50), the men who follow him should not be thoughtful, critical and caring, but rather aggressive, violent, nonverbal

(and bigoted?). This reductionist and elementary perspective may be overstated for effect but it is nevertheless a dangerous take on the

masculine ideal that Christian men should aspire to and serves to colour in the backdrop against which Eldredge introduced his own

masculine ideal. According to O’Brien (2008:50), ‘The authors don’t say so explicitly, but their rhetoric assumes

manly instincts are inherently godly’. One need not scrutinise Eldredge too closely to discover the defining attribute of his masculine ideal. As the title suggests, the most

important characteristic of this man is that he is wild at heart. It is not explicitly spelled out what exactly this means, but suffice

it to say his vision of ideal manhood involves being active and aggressive or ready to fight (though not in a violent macho way). For

Eldredge, this fight involves the way you are willing to fight for your wife on an emotional level and spend time with your children

in spite of an encroaching outside world (which may include the church) that is determined to steal their and your attention. He does

not, in other words, propose that all men become gladiators or William Wallaces, but he does seem to want to counter that other answer

to masculinity in crisis, the metrosexual. The metrosexual is born out of the 18th century flŌneur and his consumption of the

city. The term was first used in Britain in 1994 when social commentator, Mark Simpson, used the word to refer to the disposition of

modern, urbane men who embrace the dandified accoutrement of self-beautification. Simpson (2004) describes the metrosexual as: [A] young man with money to spend, living in or within easy reach of a metropolis – because that’s where all the best shops,

clubs, gyms and hairdressers are. He might be officially gay, straight or bisexual, but this is utterly immaterial because he has clearly

taken himself as his own love object and pleasure as his sexual preference.6 (Simpson 2004) Eldredge seems to sketch this pattern as detrimental to male vitality and seems determined to draw men out of salons and clubs

(and offices?) back to nature. In doing so, however, he slips into the rhetoric of active masculinity and passive femininity, a

binary articulation which reduces Christian men and women to cartoonish gendered types. It is worthy to note that no reference to the importance of a man’s appearance is made in Wild at Heart or on its cover.

This tendency coincides with Eldredge’s above discussed negation of metrosexuality, which often emphasises male appearance above

other things. The downplay of the relevance of outward appearance to masculine identity proves to be one of the most significant

contrasts between the two books and their covers, as the importance of physical beauty to feminine identity is over-emphasised,

as will be argued in the following section of this article. As for the cover of the book, one might now read the image of the

leaping protagonist as one that affirms the notion of men actively pursuing their dreams. At this, the dawn of a new day, the

masculine is cast as the heroic that must conquer his surroundings in an epic battle for his male soul. Our hero has a backpack

on his back, indicating that he is prepared for the journey he now faces alone. His isolation from the rest of the world is accented

by the untamed nature that surrounds him. Beneath him the dark mountain hints at the obstacles and dangers he will face on his

journey. For herein lies his worth, that he can overcome the looming peril. But it is not without help that he conquers the reality of a

menacing threat. The fir trees on either side of him reach up to his God recalling the pantheistic landscapes of Casper David Friedrich

that visualised the Romantic belief that God is to be found in nature. The masculine is thus in divine communion with God as he fulfils

his calling. The milieu within which this intrepid adventurer finds himself is the wild and epic outdoors. Here, on Eldredge’s cover the age-

old binary of nature being associated with the feminine and culture with the masculine is thwarted so that the civilised domain of

culture and domesticity is as threatening to the masculine as the very feminine itself. The ultimate fight, it seems, is not for a woman,

but for yourself. Eldredge deftly proposes that in order to do so every man must embark on a solitary journey that will have him leaping

from summit to summit at the dawn of his new life. The visual elements on Wild at Heart’s cover function to construct a hero-myth in relation to masculine identity by tapping into

connotations of adventurism, danger, challenge, wildness, exploration and conquering. The way in which the male figure on this cover is placed

in his surroundings, actively inspecting the landscape, cements these connotations and feeds the hero-myth. Another aspect of the hero myth is

his desire to have a beauty to rescue. This particular masculine identity construction passively positions the female as the Beauty, an object,

something to acquire, perhaps even a quest to fulfil, echoing classic Hollywood cinema. Patriarchal power is thus protected at the end of the

day. The masculine is granted Carte Blanche in terms of his right to agency and proactivity. He is commanded to do many things and act

according to his masculine will, to be wild, to fight, to live. But perhaps there is already a blotch on this blank folio, as he is symbolically

and hegemonically bound to the patriarchal rhetoric of hyper-heterosexuality.

Captivating

The cover of Captivating is to some extent read in comparison to that of Wild at Heart, as Captivating

can, arguably, be considered a supplementary text to Wild at Heart. Wild at Heart acts almost as a preface to

Captivating, as Wild at Heart, already in Chapter 1, lays out the secrets of a woman’s soul (Eldredge 2001:14–18).

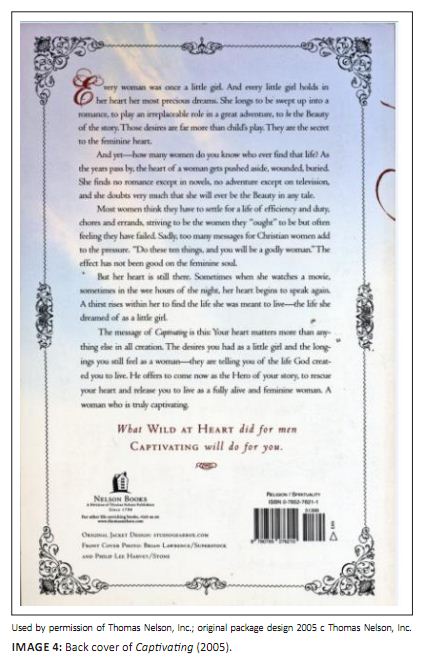

Critical Christian blogger, Tim Challies (2005), points out that Captivating’s front cover (Image 3) clearly and pertinently

refers to Wild at Heart, by citing Eldredge as ‘Best-selling author of Wild at Heart’. In a similar vein,

the back cover of Captivating (Image 4) proclaims: ‘What Wild at Heart did for men Captivating will do for

you’. Captivating furthermore quotes extensively from Wild at Heart and even includes a lengthy excerpt from

Wild at Heart towards the end of the book. Moreover, the messages of the two books can be considered to be basically the same.

Challies (2005:3 of 3) crystallises this fact with the following statement: ‘Overall, this book is little more than

Wild at Heart written for women – with a soft, feminine cover in place of the harsh, masculine one’.

|

IMAGE 3: Front cover of Captivating (2005).

|

|

|

IMAGE 4: Back cover of Captivating (2005).

|

|

When specifically considering the book covers, one finds that unlike the hero myth that is found on Wild at Heart’s cover,

Captivating’s cover makes pertinent reference to fairytale myths. Most of the formal elements, as well as constructed codes,

on this cover point to this idea and function to connect fairytale myth with feminine identity construction. As masculinity is strongly identified with adventurism, exploration and conquer on Wild at Heart’s cover, feminine identity

is here identified with nature, beauty and the ephemeral. A duality is constructed between these two covers, which feeds on the existing

active male–passive female binary in Sherry Ortner’s (1998) terms. In order to explain the universal subordination of women,

Ortner (1998:29) applies the nature–culture duality to the male–female duality and aligns male to culture and female to nature.

Although subversive of the nature or culture typology in one respect, on another level one can see that on the cover of Wild at Heart

that this male-culture alignment appears intact to the extent that the solitary boulder-jumping male figure appears as an exploring and

even conquering force in the landscape. The female figure on Captivating’s cover manifests quite differently than her male

counterpart in this regard. A solitary female figure appears in the lower left-hand corner of the cover. Unlike the active male figure,

she seems to be passively situated in nature, strolling peacefully about a field. She is not forcefully conquering the landscape she is

placed in, but blends in to form a part of it. The inherent female passivity in Captivating is already foreshadowed in

Wild at Heart, where it is stated that a man desires a beauty to rescue (Eldredge 2001:14). The female’s role is this transaction

extends only as far as being that beauty. Camery-Hogatt and Munn (2005) colourfully captures the Eldredges’ imbedded ideology of

female passivity and male activity in the following statement: Whereas the Wild at Heart man is encouraged to pursue private adventures (his erstwhile damsel-in-distress, now a conjugal prop, is only

along for the ride), a woman’s capabilities are evaluated strictly according to their effect upon her mate. (Camery-Hogatt & Munn 2005:26) Most of the visual elements on Captivating’s cover could be considered more ‘feminine’ than those found on

Wild at Heart’s cover. The text used for the book’s title is elegant and flowing as opposed to the bold stoic text

used for Wild at Heart’s title. Small fragments seem to be eroded from the lettering of the word Captivating giving

the idea that the font is fading away, fleeting and tentative. This font attribute links to other whimsical associations created on the

cover. The play of light cuts through the female figure, rendering her almost translucent. This gives the female figure a certain

whimsical, transient quality, as though she is fading away, or disappearing into the light. One could argue that this, as well as

other whimsical elements on the cover, functions to associate the feminine with the transcendental or the spiritual. The subtitle

of the book, Unveiling the Mystery of a Woman’s Soul, also betrays this agenda to associate the feminine with

the supernatural or otherworldly, by referring to the female soul as a veiled mystery, the unknown and illogical. Fairytale-like myths of princesses and castles are at work on the Captivating cover. At the lower right of the cover one sees

an easily recognisable, though blurry, castle. The female figure in the left appears to be moving towards this castle. Feminine identity

is here thus strongly and openly associated with the romantic ideas behind fairytales, castles and beautiful princesses desiring to be

rescued by their prince. The central thesis of the book is robustly linked to this visual association of the feminine to fairytale myth.

The Eldredges believe that they are ‘unveiling the mystery of a woman’s soul’ as the title suggests, which is that

every woman desires to be desired. The blurb on the book’s back cover reads: Every woman was once a little girl. And every little girl holds in her heart her most precious dreams. She longs to be swept up into a

romance, to play an irreplaceable role in a great adventure, to be the Beauty of the story. Those desires are far more than child’s

play. They are the secret to the feminine heart. (Eldredge & Eldredge 2005) The Eldredges construct femininity in monolithic, heterosexual terms, claiming truth for all women and placing heavy emphasis

on the importance of infantile romantic fantasies in an adult woman’s life. This tendency already manifests in the earlier text

of Wild at Heart, where Eldredge (2001:16) echoes the above-quoted passage: ‘Her childhood dreams of a knight in shining

armor are not girlish fantasies, they are the core of the feminine heart and the life she knows she was made for’. One cannot

help but to, again, recognise undertones of the classical Hollywood damsel-in-distress narrative. What is interesting with regard to this feminine identity construction is that it is done in relation to that of male identity. It is the

male heart, whether human or godly, which a woman is meant to captivate and it is in a man’s adventure that she is to play an

irreplaceable role and be the Beauty. Whereas Wild at Heart’s message to men is: ‘Be a real man and let them

deal with your masculinity,’ (cf. Eldredge 2001:151) the message Captivating is sending to women seems to be: ‘You

have to please men – deal with it’. Again, the feminine is already constructed in these terms in Wild at Heart, as

Eldredge (2001:16) states: ‘Every woman wants an adventure to share ... A woman doesn’t want to be the adventure;

she wants to be caught up into something greater than herself’. Implying a man’s adventure, we presume. In Captivating, the Eldredges place conspicuous emphasis on feminine physical beauty or (passively) being the Beauty in

the story, as previously mentioned. The Eldredges (2005:130) state: ‘The essence of a woman is Beauty. She is meant to be the

incarnation ... of a Captivating God ... Beauty is what the world longs to experience from a woman’. This emphasis on what seems

to be outward beauty is somewhat contradictory to mainstream Christian belief, which often downplays physical beauty in women to favour

spiritual virtue. It seems as though the Eldredges are encouraging women to strive for physically captivating beauty. Resultantly,

Camery-Hoggatt and Munn (2005:25) observes, ‘This woman’s only qualifications, it seems, are her good looks and her helplessness

– athleticism, artistic ability, erudition, and moral virtue are not taken into consideration’. This tendency of Captivating and Wild at Heart to over-emphasise feminine beauty is significant as it provides an example

of a case where Christian culture draws from mainstream culture rather than from accepted theological doctrine, as anticipated, for point

of reference. The mainstream media often portrays women as powerful as a result of sexual power derived from their physical beauty.

The Eldredges are alluding to the same idea when propagating the notion that a woman’s sole purpose is to be desired and to

captivate the attention of the masculine. This feeds into mainstream gender stereotypes of female beauty and contradicts expectations

of piety from Christian women, as described by Christina Landman (1994). Reviewer for Christianity Today, Agnieszka Tennant (2006:60), believes that the beauty the Eldredges are alluding to is not the

earth-shattering, mind-altering Beauty as found in classic and modern literature, as well as the discourse around the sublimity of beauty,

but rather ‘mere prettification, a tendency towards sentimental adornment’. Tennant (2006:60) proposes that the Eldredges are

limiting the source of beauty to women only and that their beauty is, in fact, ‘not wild enough’. In our opinion, the

Eldredges are falling into the essentialist trap of aligning the feminine with decorative ornamentation, especially on the cover of

Captivating as well as in both texts. We have already mentioned some of the decorative and whimsical elements on Captivatin

g’s cover, but the female figure’s clothing serves as a case in point. On her skirt a decorative, seemingly flowery, pattern

becomes visible and her head is adorned with a translucent, bridal veil-like scarf or head wrap. There is much discourse around the

alignment of the female with decoration and craft or ‘low-culture’, versus the alignment of the masculine with abstraction

(the opposite of decoration in artistic terms) and art or ‘high-culture’,7 which for the sake of brevity we will

not venture into. It would suffice to say that the Eldredges are most visually participating in this binary alignment of the feminine to

the decorative, which corresponds to the female-nature-passivity construct explored earlier. The female figure on Captivating’s

cover and perhaps in the two texts as well, appears as decorative ornament, sentimentally floating through the landscape. A final issue to be raised about Captivating is that of the sexual undertones of the proposed unveiling of the mystery of a

woman’s soul. A few bloggers have picked up on Wild at Heart and Captivating’s sexualisation of the female,

most notably Challies (2005) and Camery-Hogatt and Munn (2005). Challies (2005) cites the following passage from Captivating

(Eldredge & Eldredge 2005) in order to critique the Eldredges’ belief that ‘God has a deep, fiery passionate love

for women and that he wishes to romance us [sic]’: Let’s go back for a moment to the movies that you love. Think of one of the most romantic scenes you can remember, scenes that

made you sigh. Jack with Rose on the bow of the Titanic, his arms around her waist, their first kiss. Wallace speaking in French to

Murron, then in Italian: ‘‘Not as beautiful as you’’. Aragorn standing with Arwen in the moonlight on the

bridge in Rivendell ... Now, put yourself in the scene as the Beauty, and Jesus as the Lover. (Eldredge & Eldredge 2005:113) The previous, for Challies (2005), ‘clearly goes beyond the biblical metaphors for God’s love’. We would suggest that

passages such as the previous not only sexually objectifies women, but goes as far as to suggest Jesus Christ himself as an erotic lover to

the female, which clearly goes beyond the metaphors most of us hold for the Christ-figure. Camery-Hoggatt and Munn (2005:25) implies that

female agency, in terms of the books, resides solely within sexuality, by stating that, ‘[t]he only area of endeavour in which the

model Wild at Heart woman is granted proactivity, apparently, is sex ...’ The Wild at heart and Captivating

woman is sketched, extremely paradoxically, as a seductress. ‘[S]he can use all she has as a woman to get him to use all he’s

got as a man. She can arouse, inspire, energize ... seduce him. Ask your man what he’d prefer’ (Eldredge 2001:192).8

Here one finds, at best, an eschewed view on Christian sexuality, again rather drawing on mainstream culture, than on theology. The above passification, subordination and sexualisation of the feminine in Wild at Heart and Captivating, ultimately

leads to gross negation of female agency and leads to dependence on and infatuation with the masculine, which mirrors the passification,

subordination and sexualisation of the feminine in mainstream patriarchal ideology. Eldredge (2001:17) makes no secret of his alignment

with an ideology of female passification: ‘The world kills a woman’s heart when it tells her to be tough, efficient and

independent’. Surely the many feminist activists from Simone de Beauvoir to Lucy Irigaray would strongly disagree with this statement.

Can women not also be ‘wild at heart’ or are they merely meant to be ‘wild at home’, as Camery-Hoggatt and Munn

(2005:25) so eloquently put it? One must acknowledge that Captivating does put itself ‘out there’ in attempting to provide guidance for Christian

women in their expected gender roles. Campbell (2007:52), however, points to the fact that, ‘the book, like so many others in its

genre, gives only perfunctory answers to the more vexing questions about women and religion today.’ Captivating does

indeed almost entirely ignore issues around biblical gender egalitarianism, the feminist problematic of women’s roles and

purpose in patriarchal churches, as well the subsequent turn to goddess worship and this seems to be a dramatic absence given the

purpose of the book. It is also necessary to note that neither Wild at Heart nor Captivating considers alternative

sexualities, such as homosexuality, bisexuality and transsexuality, as options for Christian men and women in their quest for answers

regarding the nature of their sex roles in spiritual and secular society.

Both of the images on the book covers discussed are photographic and perhaps it is worth taking a moment to discuss the theoretical

implications of this medium being used here. Susan Sontag (2008:4) has noted that ‘Photographic images do not seem to be statements

about the world so much as pieces of it, miniatures of reality that anyone can make or acquire.’ For her, then, ‘photographs

furnish evidence’ (Sontag 2008:5). ‘[T]he camera record justifies’ (Sontag 2008: 5). Perhaps this means that the book

covers discussed in this article are not merely statements about the authors intent regarding the meaning of gender, but statements about

the manner in which gender functions in reality. They are not just codes but are a reality themselves, a coded moment of reality

meant, in Hall’s terms to be decoded and thus, internalised. Again, Sontag (2008: 8) deems photography ‘a social rite, a

defence against anxiety, and a tool of power’. She comments that through photographs families construct a portrait chronicle of

themselves – ‘a portable kit of images that bears witness to its connectedness’ (Sontag 2008:8). In Homi Bhabha’s

(1994) terms, photographic imagery may thus serve as a connective narrative binding together families or, as in this case, a community.

And herein lies the rub. Do the Eldredges’ book covers provide a portrait of the Christian family that is stereotypical at best

and prescriptive at worst? This article posed the question whether the visual semiotics of the cover art of Wild at Heart and Captivating further

enshrine the gender stereotypes found in mainstream popular Christian media. Through an analysis of these visual texts it was found

that the codes used in the covers continue the binary reading of gender that is established within secular media and do so within the

seemingly authoritative context of the sublime. These books and their covers thus serve as prescriptive texts on how Christian gender

should be performed in society. We also found that, in this case, popular secular mainstream media influences popular Christian media

to a great extent, as the Eldredges’ ‘theology’ is rather based on Hollywood than on a biblical model of gender. It

could perhaps then be argued that owing to this tendency mainstream gender stereotypes are also further solidified. As mentioned earlier, we do not suggest a definitive reading of these covers, but a reading, amongst many possible readings,

about the meanings constructed, ideologies conveyed and realities created by these covers at Hall (1980) and Corner’s (1983)

moment of encoding, moment of the text and moment of decoding, which strictly speaking implies the position of the reader, but is

also already forecast by the text’s encoding and own textuality. For the purpose of this article we were interested in the way the Eldredges’ theses are translated into visual terms on the

covers of the two books in question, as well as in how gender is represented on the covers and how they are constructing gendered

Christian identity. As mentioned earlier, the visuality of Christian culture is important subject matter for media theorists, not

least because Christian visual media must influence Christian culture and not just the other way around. In conclusion, we maintain

that the manner in which beliefs about gendered sex roles are communicated through the visual material promoting itself as ‘

Christian’ in the hegemonic sense demands further analysis from a secular (feminist) perspective as well as in terms of the

cultural ‘meanings’ of visual imagery within Western society. For us, both book covers are complicit in making the gendered

reality represented in these books atomic, manageable and opaque. ‘It is a view of the world which denies interconnectedness,

continuity, but which confers on each moment the character of a mystery’ (Sontag 2008:23).

Arendt, H. (ed.), 1968, Illuminations, transl. H. Zohn, Schocken Books, New York. Arnold, M. & Schmahmann, B., 2005, Between union and liberation. Women artists in South Africa 1910–1994,

Ashgate, Aldershot. Bhabha, H.K., 1994, The location of culture, Routledge, London & New York. Barthes, R., 1972, Mythologies, transl. A. Lavers, Paladin, London. Barthes, R., 1979, Image-music-text, transl. S. Heath, Glasgow, Fontana/Collins. Benjamin, W., [1935] 1968, ‘The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction’, in H. Arendt (ed.), Illuminations,

transl. H. Zohn, pp. 217–252, Schocken Books, New York. Bignell, J., 2002, Media semiotics. An introduction, 2nd edn., Manchester University Press, Manchester & New York. Brandt, R., 2003, ‘Wild at Heart: Discovering the secret of a man’s soul. By John Eldredge’ in Contend4TheFaith,

viewed 07 July 2009, from http://blogspy.com/contend/bookWild.html Broude, N., 1982, ‘Miriam Shapiro and “femmage”: Reflections on the conflict between decoration and abstraction in twentieth-

century art’, in N. Broude & M.D. Garrard (eds.), Feminism and art history: questioning the litany, pp. 315–330,

Harper & Row, New York. Broude, N. & Garrard, M.D. (eds.), 1982, Feminism and art history: questioning the litany, Harper & Row, New York. Broude, N. & Garrard, M.D. (eds.), 1992, The expanding discourse. Feminism and Art history, Icon, New York. Broude, N. & Garrard, M.D. (eds.), 2005, Reclaiming female agency. Feminist art history after postmodernism, University of

California Press, Berkeley. Camery-Hoggatt, B. & Munn, N., 2005, ‘Wild at heart: Essential reading or “junk food for the soul”?’,

Priscilla Papers 19(4), 24–26. Campbell, C.C., 2007, ‘God and the second sex’, First things: a monthly journal of religion and public life 176:51–56. Challies, T., 2004, ‘Book review- Wild at Heart’; in Challies.com, viewed 07 July 2009, from

http://www.challies.com/archives/general-news/book-review-wil.php Challies, T., 2005, ‘Book review- Captivating’, in Challies.com, viewed 07 July 2009, from,

http://www.challies.com/book-reviews/book-review-captivating Chandler, D., 1994, ‘Encoding/Decoding’, in Semiotics for Beginners, viewed 20 November 2010, from

http://www.aber.ac.uk/media/Documents/S4B/sem08c.html

Clare, A., 2000, On Men: Masculinity in Crisis, Chatto & Windus, London. Corner, J., 1983, ‘Textuality, Communication and Power’, in H. Davis & P. Walton (eds.), Language,

Image, Media, pp. 266–281, Basil Blackwell, Oxford. Eldredge, J., 2001, Wild at Heart. Discovering the secret of a man’s soul, Thomas Nelson, Nashville, T.N. Eldredge, J. & Eldredge, S., 2005, Captivating. Unveiling the mystery of a woman’s soul, Thomas Nelson, Nashville, T.N. Gallagher, S.K. & Wood, S.L., 2005, ‘Godly manhood gone wild?: Transformations in conservative protestant masculinity’,

Sociology of religion 66(2), 135–160. doi:10.2307/4153083 Gibson, M. (dir.), 1995, Braveheart, Paramount Pictures Corporation, Hollywood, CA. Gouma-Peterson, T. & Matthews, P., 1987, ‘The feminist critique of art history’, The art bulletin LXIX(3),

326–357. doi:10.2307/3051059 Haddad, M., 2009, ‘Women who were wild at heart’, in Sojourners, viewed 07 July 2009, from

http://blog.sojo.net/2009/05/11/women-who-were-wild-at-heart/ Hagenau, S., 2009, email, 28 October, SHagenau@thomasnelson.com Hall, S., 1980, ‘Encoding/Decoding*’, in S. Hall, D. Hobson, A. Lowe & P. Willis (eds.), Culture, media, language,

pp. 166–176, Hutchinson, London. Landman, C., 1994, The piety of Afrikaans women. Diaries of guilt, University of South Africa, Pretoria. LeBlanc, D., 2004, ‘Wild heart’, Christianity today, August, 30–36. Murrow, D., 2005, Why men hate going to church, Thomas Nelson, Nashville, T.N. Nead, L., 1992, The female nude: Art, obscenity and sexuality, Routledge, London.

doi:10.4324/9780203328194 Nixon, S., 1996, Hard looks, masculinities, spectatorship and contemporary Consumption, University of California Press &

St. Martin’s, New York. Nochlin, L., [1971] 1989, ‘Why have there been no great women artists?’ in L. Nochlin (ed.), Women, art, and power,

and other essays, pp. 145–178, Thames & Hudson, London. Nochlin, L. (ed.), 1989, Women, art, and power, and other essays. Thames & Hudson, London. O’Brien, B., 2008, ‘A Jesus for real men. What the masculinity movement gets right and wrong’, Christianity

today, April, 49–52. Ortner, S.B., 1998, ‘Is female to male as nature is to culture?’ in L.J. Peach (ed.), Women in culture.

A women’s studies anthology, pp. 23–44, Blackwell , Oxford. Owens, C., 1992, ‘The discourse of others. Feminists and Postmodernism’, in S. Bryson, B. Kruger, L. Tillman &

J. Weinstock (eds.), Beyond recognition. Representation, power and culture, pp. 166–186, University of California

Press, Berkeley & Los Angeles. Parker, R. & Pollock, G., 1981, Old mistresses. Women, art and ideology, Routledge, London. Payne, L., 1978, Crisis in masculinity, Crossway, Wheaton. Peach, L.J. (ed.), 1998, Women in culture. A women’s studies anthology, Blackwell, Oxford. Ransomed Heart Ministries, 2009, Who we are, viewed 30 June 2009, from

http://www.ransomedheart.com/ministry/who-we-are.aspx Simpson, M., 2004, ‘MetroDaddy speaks’, in Mark Simpson.com, viewed 19 June 2006, from,

http://www.marksimpson.com/pages/journalism/metrodaddyspeaks.html Sontag, S., [1971] 2008, On photography, Penguin, London. Tennant, A., 2006, ‘What (not all) women want. The finicky femininity of Captivating by John and Stasi Eldredge’,

Christianity Today, August, 60. Wallechinsky, D. & Wallace, I., 2009, ‘Origins of Sayings - The Mass of Men Lead Lives of Quiet Desperation’, in

Trivia Library, viewed 24 November 2009, from

http://www.trivia-library.com/b/origins-of-sayings-the-mass-of-men-lead-lives-of-quiet-desperation.htm Wingerd, D., n.d., ‘A critical review of the book, Wild at Heart, by John Eldredge’, in Christian Communications Worldwide,

viewed 30 June 2009, from http://www.ccwonline.org/wild.html Winslow, L., 2007, ‘Naturally uncivilized: Locating the subject position in Wild at heart’, paper presented at the 93rd annual

National Communication Association convention, Hilton & Towers Palmer House Hilton, Chicago, I.L, 15–18th November.

1.It is questionable whether this success is as a result of effective marketing or theological

merit, as Brynn Camery-Hoggatt and NelsonMunn (2005:24) points out: ’Eldredge’s immense popularity ... must not be allowed

to disguise the fact that his suggestions are often incongruent with the teachings of Jesus’. Blogger, Randy Brandt (2003)

says that Eldredge is propagating a theologically suspect stream of thought called Open Theism, a movement which is known for

denying God’s omniscience, omnipotence and sovereignty, ultimately resulting in the humanising of God. 2.Wild at Heart does, however, spark fervent criticism amongst bloggers and book reviewers (cf. Brandt 2003, LeBlanc

2004, Challies 2004 & 2005; Winslow 2007, O’Brien 2008; Haddad 2009; Wingerd n.d.). Captivating enjoys

notably less attention from these spheres as can be seen in the smaller number of blog-posts and book reviews attributed

to Captivating (cf. Challies 2005, Tennant 2006, Campbell 2007).

3.For summaries of the theological concerns about the books see Wingerd (n.d.), Winslow (2007), Camery-Hoggatt and Munn (2005) and

Challies (2005).

4.American philosopher and naturalist Thoreau isolated himself at Walden Pond in Massachusetts from 1845 to 1847. His experiences

during that time were published in Walden (1854). In a well-known passage, Thoreau stated his purpose: ‘I went to the woods

because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach,

and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived. I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear; nor did

I wish to practice resignation ...’ In the first essay, ‘Economy’, Thoreau comments that most men are slaves to

their work and enslaved to those for whom they work. He concludes: ‘The mass of men lead lives of quiet desperation.

What is called resignation is confirmed desperation ...’ (Wallechinsky & Wallace 2009). This passage indicates

that Thoreau identified a crisis in masculinity even then and related this to the manner in which Western male identity is

connected to work or fiscal productivity. This connection would later be teased out by theorists such as Leanne Payne (1978)

and Anthony Clare (2000). 5.From all accounts, it seems that the historical Jesus did, in fact, wear a ‘dress’. 6.Metrosexuality has, subsequently, become a part of the aspirational syntax of popular media like men’s lifestyle magazines

that aim to procure the support of high end advertisers and in doing so endorse the connection between masculinity and consumption.

This phenomenon is not overtly present in all South African media, seems, increasingly, to be an important signifier in the

redefining of masculine identity in this context, particularly considering the fact that ‘modern forms of consumption privilege

certain public masculinities as the subject of the look’ (Nixon 1996:70).

7.See, amongst others, Nochlin (1971), Parker and Pollock (1981), Broude (1982),

Broude and Garrard (eds. 1982, 1992 & 2005) Gouma-Peterson and Matthews

(1987), Owens (1992) and Arnold and Schmahmann (2005).

8.This quotation refers to EldredgeÆs (2001:191¢192) passage on RuthÆs seduction of

Boaz, where he antithetically sates: æThis seduction is pure and simple ¢ and God

holds it up for all women to follow when he not only gives Ruth her own book in the

Bible but also names her in the genealogyÆ.

|